Special project

Special project

settlements

Is Israel occupying territory? How did the settlements come to exist? Are they legal or not? What is happening today?

Photo: Reuters, Amir Cohen

Introduction. What Happened.

On July 19, the UN International Court of Justice issued yet another unfavorable opinion for Israel, addressing the legal status of its military control and settlements in the West Bank (Judea and Samaria). This ruling is separate from the ongoing conflict and South Africa’s parallel proceedings against Israel. The UN General Assembly, with a majority of 83 votes, had requested an advisory opinion on this matter back in December 2022.

* For simplicity, we will not be addressing the Gaza Strip in this discussion.

What did the court rule?

- That Israel’s presence in the West Bank, including annexed East Jerusalem, is deemed illegal and must end as soon as possible;

- that Israel must halt settlement expansion, eventually dismantle all settlements, and provide reparations to the local population;

- that the international community has an obligation not to recognize Israel’s presence in these territories, and that the UN must consider further actions to counter it.

This is not the first time the UN and its affiliated organizations have declared Israel’s control and presence in the West Bank an illegal occupation. Numerous General Assembly and Security Council resolutions have reiterated this stance, with the most recent being Resolution 2334 in 2016 (which passed due to the absence of a US veto). The UN International Court of Justice also addressed this issue back in 2004 when it ruled on the illegality of the separation fence and other aspects of Israel’s control over the disputed territories.

What sets the current ruling apart? Firstly, the question has been answered unequivocally once again.

Secondly, for the first time, the court explicitly warns third countries against cooperating with Israeli settlements and calls for distinguishing between cooperation with Israel within its internationally recognized borders and activities beyond them.

Third, the timing of the ruling is particularly problematic for Israel. With much of the world’s attention still focused on us, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and its complex aspects are once again at the forefront. Although the ruling is not directly related to the war in Gaza, it nevertheless coincides with several significant developments:

- A parallel genocide trial;

- The threat of arrest warrants against the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defense by the International Criminal Court;

- Unilateral recognition of Palestinian statehood by several countries;

- A series of sanctions imposed on individuals and settlement organizations by the US, Canada, the UK, France, Australia, Japan, and the EU.

Perhaps if the war ends in the foreseeable future and the world’s attention shifts back to something else, the effects of this decision will be less tangible in the short term. However, the long-term damage is undoubtedly done; this ruling will be followed by others, and it is naive to expect that the world will immediately forget such a long, bloody war and the century-long conflict behind it.

These and other legal processes developed in recent decades will continue to be a lever of severe pressure on Israel that requires cautious attention and wise policies.

In the meantime, the court’s ruling marks yet another diplomatic blunder stemming from a siege-mentality approach, where all criticism is outright dismissed as slander and one’s own righteousness remains unquestioned. The decision triggered a wave of counter-accusations of anti-Semitism and support for terrorism from across Israel’s political spectrum, including opposition leaders.

However, setting aside the ludicrous reactions of our politicians and focusing on the substance of the decision, one must ask: Does the court’s ruling have merit and solid foundations, and what is the official Israeli stance on this highly controversial issue?

Having studied numerous opinions, documents, and conclusions, we explore the legal aspects of the issue, offer a historical overview, present various perspectives on Israeli settlements, analyze the Israeli position, and raise challenging questions that are becoming much less frequently discussed in Israeli society.

Note This is a long piece. You may want to save it and read it in parts.

Does Israel occupy the territory?

Israel’s internationally recognized border is the so-called Green Line, established after the 1948-1949 Arab-Israeli War (War of Independence). Following the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel took control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip (from Egypt), East Jerusalem and the West Bank (Judea and Samaria, from Jordan), and the Golan Heights (from Syria).

The Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt as part of a peace treaty, while the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem were unilaterally annexed by Israel. The Gaza Strip and the West Bank (Judea and Samaria) remained under Israeli control without formal status for some time.

Let us first examine one of the theoretical Israeli approaches, as outlined in the 2012 report on the legal status of construction in Judea and Samaria. This report was prepared by an informal commission led by former Supreme Court Justice Edmund Levy.

This approach is based on several key premises:

- Due to the Arab rejection of the Palestine Partition Plan (1947), the Gaza Strip and the West Bank lacked legal state status and were subsequently occupied by Egypt and Jordan during the 1948-1949 war (with Jordan’s annexation of the West Bank not being internationally recognized).

- Since these territories did not have a universally recognized status at the time of their capture, and with Egypt and Jordan later renouncing their claims, Israel’s acquisition of these areas during the defensive war in June 1967 did not involve seizing sovereign territory from another state.

Based on these premises, the argument concludes that Israel did not occupy sovereign territory but rather a disputed area with no internationally recognized status. Consequently, it cannot be classified as an occupation under international law. Instead, the territories are considered to have a unique status, and international conventions regulating occupations do not apply. This view suggests that Israel has the authority to manage these territories as it sees fit.

This approach stands in stark contrast to the position of the international community, the majority of countries, and many Israeli and international legal experts. It also somewhat contradicts Israel’s semi-official stance since 1967, numerous Supreme Court rulings, and the state’s actual practices. Let’s examine this in detail.

According to Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Convention, a territory is deemed occupied when it is effectively controlled by foreign military forces, hostile to the local population.

We have to differentiate between the everyday meanings of terms and their legal implications, which often do not evaluate specific circumstances. For instance, the term “occupation” does not automatically carry a negative connotation. It can refer to situations where territory is controlled as part of a defensive action, such as the temporary occupation of Germany by Allied forces after World War II.

Nonetheless, already in early Israeli legal documents, the term ‘occupation’ was intentionally replaced with the more neutral term ‘controlled territories.’ Meir Shamgar, who served as a military prosecutor, legal advisor to the government, and later as president of the Supreme Court, developed this framework. He argued that since the territory’s status was unresolved before the war, conventional laws of occupation could not be strictly applied. Instead, the territory should be managed within a relatively flexible legal framework.

Whatever we choose to call it, subsequent Supreme Court decisions and opinions from the state’s legal advisers consistently reference the norms of international law governing occupation. In practice, even though the term ‘occupation’ is avoided, the state operates within its framework.

We could endlessly delve into legal nuances and loopholes, weighing certain arguments over others. Perhaps this was more siutable in the late 1960s, when the future was less certain and it was easier to juggle the shifting geopolitical and legal aspects.

But let us leverage our position as witnesses and participants in the sixth decade of this ‘temporary’ situation to answer the question directly: Yes, Israel is indeed occupying the territory. Israel has not extended its sovereignty to these areas but governs a large population with the aid of its military, interpreting international law rather broadly, yet trying to operate within its framework. Furthermore, this is the position of virtually the entire world, and we are not living on some distant island.

International law is specifically designed to address such situations, offering legal protection to the occupied population and defining the permissible and impermissible actions for the occupying power.

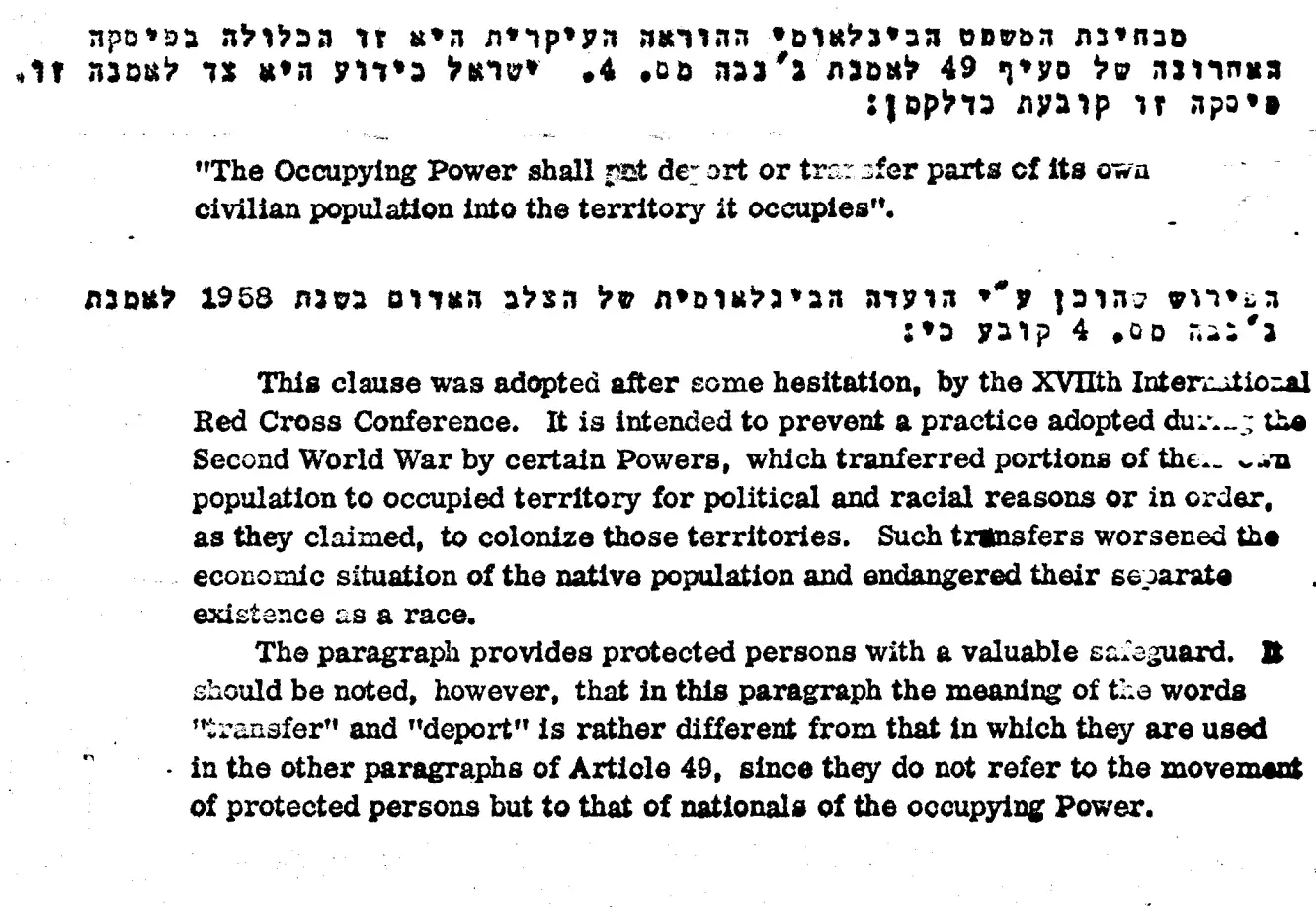

For instance, Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention explicitly prohibits the forced transfer or deportation of the local population, as well as the relocation of the occupying state’s own citizens to the occupied territory. At first glance, this seems to directly contradict settlement activities. But let’s break it down.

How did the settlements come about and are they legal?

Legal basis?

The victory in the Six-Day War sparked widespread euphoria in Israeli society, giving a new impulse to settlement ethos and the image of Zionist pioneers. What is often forgotten in the current political reality is that this new settlement movement was not the exclusive domain of right-wing and religious circles at the beginning. The first decades of the settlements were actively supported by left-wing governments and elites of the labor movement, including big names such as Natan Alterman, Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, Yitzhak Tabenkin and others. The new generation settlers were then portrayed as the inheritors of the Zionist project.

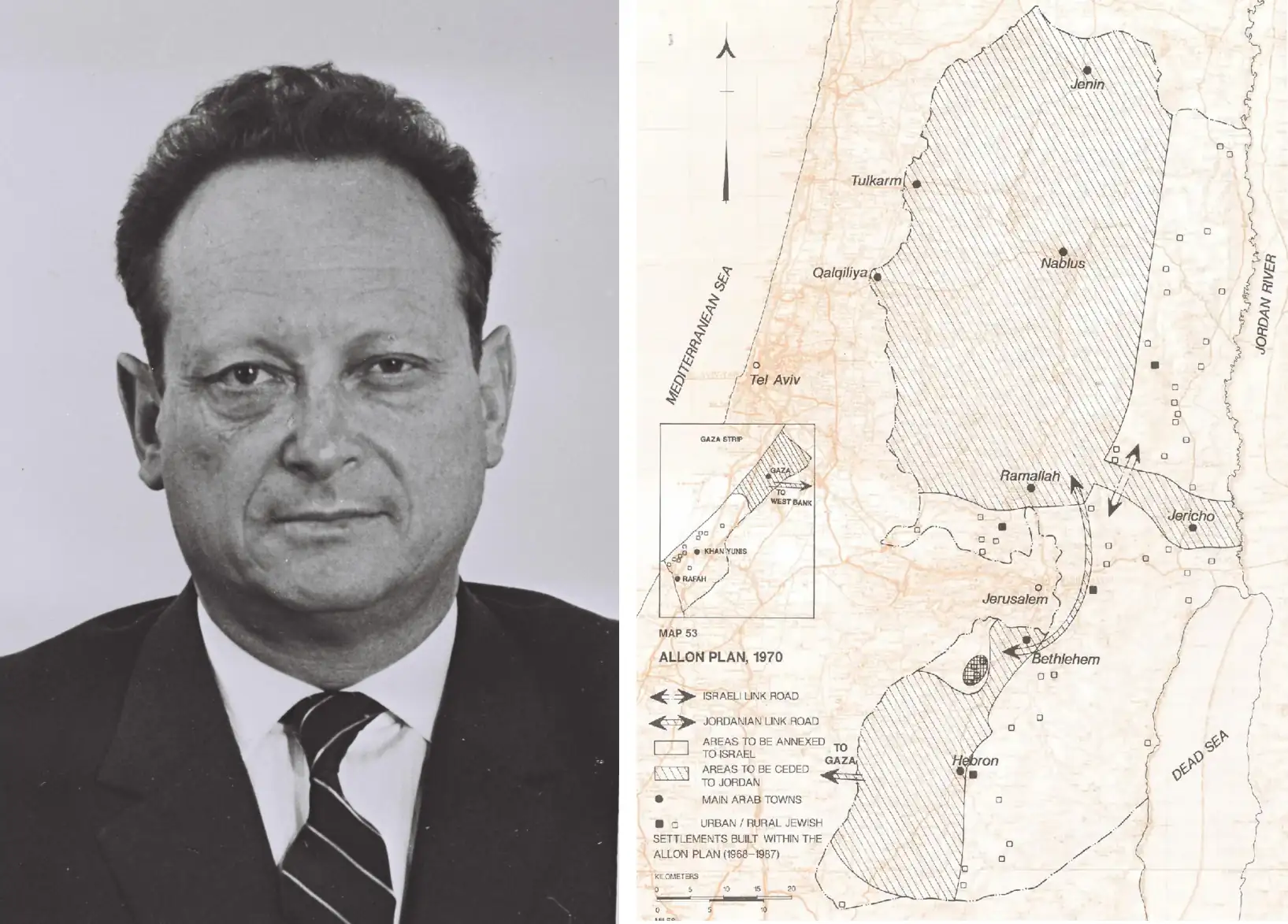

Besides the cultural aspect, settling and potentially annexing parts of the conquered territories also gained considerable political traction. This strategy was partly driven by a desire to enhance Israel’s security and defensive posture against future threats. For instance, Israeli leaders were concerned about the vulnerability of the new eastern border with Jordan, where the stability of Israel’s favored Hashemite monarchy was never a guarantee. Retired General and minister at the time, Yigal Alon, proposed a bold plan to annex most of the West Bank, including the entire Jordan Valley, although this plan has never come to fruition.

Either way, those various ambitions and plans needed some legal foundation. At that time, a presumptive interpretation of the Geneva Convention suggested that if individuals rather than the state initiated settlement activity, it might circumvent the prohibition.

However, this assumption was refuted in 1967 by Theodor Meron, a legal advisor to the Israeli Foreign Ministry and distinguished international law expert, later a judge at several international tribunals and a professor at Harvard and Berkeley. At the request of the Prime Minister’s advisor, Meron provided a legal assessment of the settlements, clearly rejecting the notion that individual initiatives could override the Geneva Convention’s restrictions.

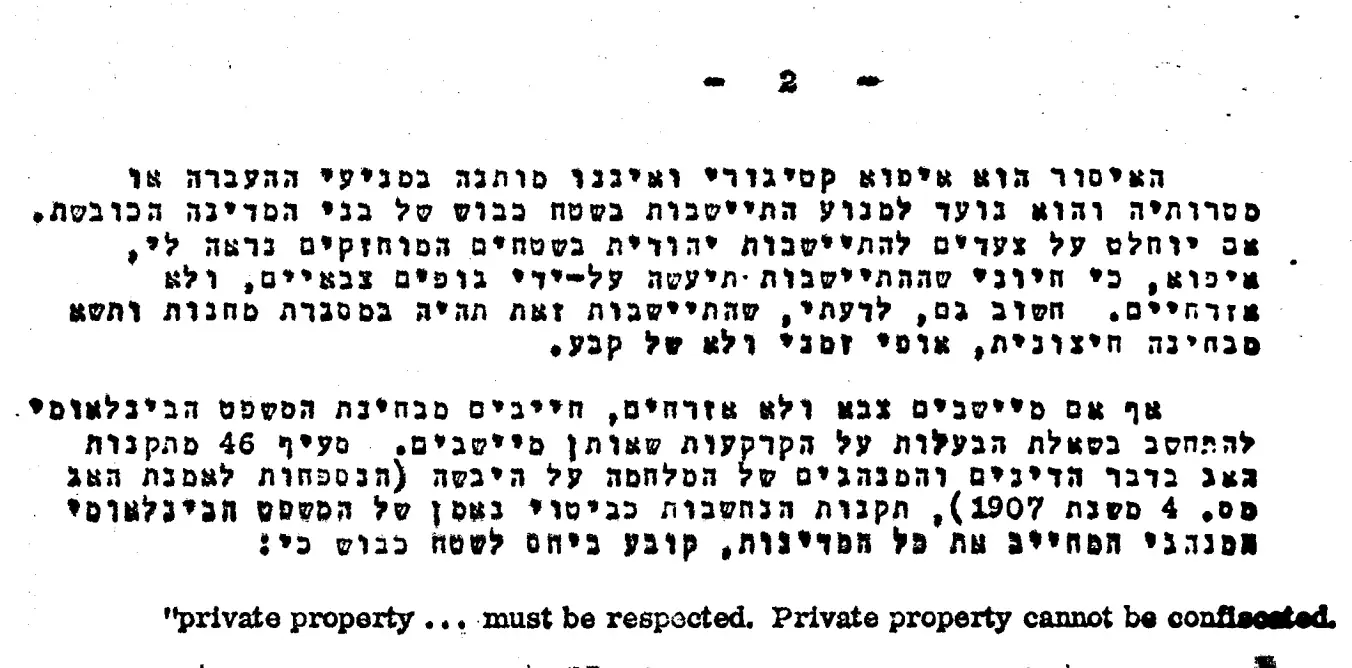

Meron argues that, in his view, all civilian settlements are in clear violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, regardless of their purpose or rationale. However, he suggests that if a government opts to permit such settlements, it must follow two crucial principles: the settlements should be established by military authorities only, and they should be explicitly temporary rather than permanent. Meron also underscores the necessity of respecting private property rights.

1967-1979 First wave: military confiscations

From Israel’s perspective, military considerations and the conditional nature of temporality provided a legal justification for establishing numerous settlements in the decade following the Six-Day War. This rationale was accepted and even further developed by the Supreme Court, with several significant rulings emerging in the 1970s.

In 1972, a direct military order from Southern District Commander Ariel Sharon and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan led to the expulsion of thousands of Bedouins — approximately five thousand according to army estimates — from the Egyptian part of Rafah to pave the way for the construction of the future port city of Yamit.

Notably, Oded Livshitz, a journalist and co-founder of Kibbutz Nir Oz who has been held hostage by Hamas since October 7, was actively involved in advocating for the rights of those displaced by this operation.

The Supreme Court rejected the petition, endorsing the Army’s security rationale based on a confidential military report.

The settlement of Yamit was evacuated and dismantled a decade later, in 1982, as part of the peace agreement with Egypt.

The fundamental and unresolved question, both then and now, is to what extent the establishment of civilian settlements can serve as an effective and legitimate means of achieving security —and, more importantly, whose security?

This is how Supreme Court Justice Alfred Witkon saw this controversy at the time:

From a security perspective, it is clear that the presence of settlements by citizens of the administering power in the occupied territory plays a significant role in enhancing security and supporting the army’s operations. It is easier for terrorist groups to operate in areas where the local population is indifferent or supportive of the enemy. In contrast, having residents who are committed to monitoring and reporting suspicious activities to the authorities can make it much harder for terrorists to find refuge or assistance.

Alfred Witkon, Supremу Сourt Justice

In 1978, the Supreme Court addressed the case of the Beit El settlement, which was established on private land. Once again, the Court dismissed the petition of the affected parties, endorsing the army’s security arguments. However, it outlined key conditions under which land expropriation could be deemed acceptable: the land must be acquired on a temporary lease basis, the lease should last only as long as the military administration is in place, and the landowner must receive fair compensation.

However, in 1979, the Supreme Court made a groundbreaking ruling declaring the Elon Moreh settlement illegal and ordering its dismantling. This decision came in response to a petition by the villagers of Rujeib, whose farmland had been expropriated for the settlement purposes. The petition was supported by opinions from retired military officials, who argued that the settlement had no significant security value.

These opinions were disputed by Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan but were supported by prominent government figures with extensive military backgrounds, such as Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, and Deputy Prime Minister Yigael Yadin. Furthermore, the settlers’ testimony indicated their intent to establish permanent settlements based on their religious beliefs. This commitment to long-term settlement, which directly contradicted the requirement for temporary land use, left the judges with no alternative but to declare the settlement illegal.

Using security concerns as the basis for land confiscation can only imply that such decisions are meant to be temporary. We firmly reject this alarming conclusion, as it contradicts the government’s intent for our settlement. Based on numerous assurances from government ministers and, most importantly, the Prime Minister himself, it is clear that Elon Moreh is intended to be a permanent Jewish settlement, no less than Dganiya or Netanya.

Menachem Felix, leader of the Gush Emunim settlement movement

The Elon Moreh settlement was dismantled but later moved to another location, not so far from the same village of Rujeib.

It is worth mentioning that these are just the cases that made it to court. Practically, there were more confiscations, clashes, and controversies. Doubts arose about the sincerity of the approach and whether military directives were being manipulated to provide legal cover for settlement ambitions. This concern was heightened by the fact that, at the time, the highest military and ministerial positions were held by individuals who openly supported the settlement movement. It’s worth remembering that, during the first decade, there was near-total political consensus on this issue.

In any case, the desire to expand settlements amid global criticism and Palestinian resistance, especially following the Elon Moreh case, highlighted the need for a new, more adaptable, and less confrontational approach. It became clear that relying solely on military justifications for settlements was no longer sufficient.

As Shlomo Gazit, the first coordinator of government actions in the controlled territories, put in his book Trapped Fools (1999):

The court’s ruling in the Elon Moreh case only advanced the government’s agenda. It ended a process in which, for around 11 years, the government had hidden its true intentions behind the pretext of dubious security needs.

Shlomo Gazit, First Coordinator of Government Activities in the Controlled Territories

In the first decade, several dozen settlements were established under the guise of military considerations. It should be noted that neither these nor any subsequent legal justifications for settlement activities were ever recognized as valid by the international community.

1979-1991 Second wave: ‘state’ land

At least until 2003*, the settlements had a ‘father’ and a ‘mother.’ The father was often referred to as Ariel Sharon, the glorious retired military officer who became Minister of Agriculture in Menachem Begin’s first government in 1977. He openly supported and actively encouraged the settlement project.

* In 2003, Sharon presented his plan for a unilateral withdrawal from Gaza and said at the government meeting as follows:

“Does anyone else think it’s okay to keep 3.5 million Palestinians under occupation? Yes, it is an occupation. You can dislike the word, but it is what it is – an occupation. In my opinion, continuing it is a terrible idea. It can’t go on without end. Do you want to stay in Shechem, Jenin, Ramallah forever? I don’t think it’s right anymore.”

Ariel Sharon, Israeli PM

However, back in 1979, following the Elon Moreh affair, it was Sharon who convened a special meeting where the idea of revising the land registry of the administered territories was conceived. The land registration system, inherited from the Turks, the British, and later the Jordanians, was imperfect and chaotic, leaving room for flexibility in interpreting public and private property.

The idea was to reassess the land and re-map the areas based on the Ottoman Land Law of 1858. According to this law, any land that remained undeveloped and uncultivated for at least three years, and was situated far enough from the nearest settlement that the sound of a rooster or a human voice could no longer be heard (approximately 2.5 km), would be automatically designated as “dead land” (mauwat) and considered state property. This designation was distinct from land that was built up, cultivated, or used as grazing pastures.

The ‘mother’ of the settlements was often referred to as Plia Albeck, who conducted that very mapping and aerial survey.

Israeli military lawyers took a very flexible approach to interpreting the Ottoman land laws, often to the detriment of existing or potential Palestinian landowners. Consequently, Israel, having inherited around 700,000 dunams of state land from the Jordanians, subsequently declared at least as much land as state property, though estimates of the additional land vary.

The idea, according to Albeck herself, was to ensure that the land used for settlements was classified as public land, thereby avoiding any infringement on individual property rights.

However, the beautiful wording hides some obvious issues with this approach. First, as noted earlier, the designation of lands as state property relied on an exceptionally broad and favorable interpretation of the old law, heavily skewed in favor of the state.

Secondly, the wording itself might suggest that since the land is proclaimed as state-owned, the state has carte blanche to use it as it pleases. This perspective ignores the fact that the land is within a disputed territory, under military control/occupation, and the “state” in this context is essentially the army. International law, therefore, requires that such lands be used either solely for military needs or for the benefit of the local population. But in no case is it for creating civilian settlements within the heart of this contested region.

Note In 2013, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel pushed for the publication of updated official figures, according to which at the time of publication 1.3 million dunams were considered state-owned, of which over the years 40% were allocated to Jewish settlements and only 0.7% were allocated to Palestinian development.

Either way, most of the settlement construction in the subsequent decade took place on these designated ‘state’ lands.

Without delving into the political intricacies or the nuances of declaring land as state-owned, the Supreme Court did not address the fundamental legality of the whole scheme. Instead, it adopted a general stance: as long as the military, rather than civilian authorities, administers the land in the controlled territories, it has the discretion to manage and allocate these lands within certain limits, such as leasing them out.

Contrary to today’s claims of ‘decades-long judicial activism,’ the Supreme Court has consistently taken a conservative stance on the issue of settlements. Over the years, justices have largely avoided interfering with state policy or issuing significant rulings, intervening only when settlement activities directly violated private rights.

Nevertheless, in nearly all judicial opinions on the subject, there is a consistent emphasis on the temporary nature of the provision. In his 1982 ruling, Judge Aaron Barak stressed that even substantial investments in infrastructure should consider the provisional nature of the situation. He highlighted that such infrastructure should ultimately benefit the local population, even after the end of military administration. At the time of that ruling, the “interim state of affairs” had lasted only 15 years, and few could have anticipated it extending for at least another 42 years.

Even Plia Albeck, who proudly referred to the settlements as “her children,” emphasized in a 2005 interview with Haaretz, commenting on the withdrawal from Gaza, that all agreements with settlers always included a component of temporariness. She noted that everyone was aware from the outset that, under certain conditions, one might have to leave.

In practice, however, the settlers’ attitude remained unchanged since the testimony in Elon Moreh case. No one really considered setllements as temporary. The era of makeshift structures on desert hills had long passed; the settlements were evolving from temporary structures into permanent communities. The basic blocks of houses formed into blocks of settlements and entire cities.

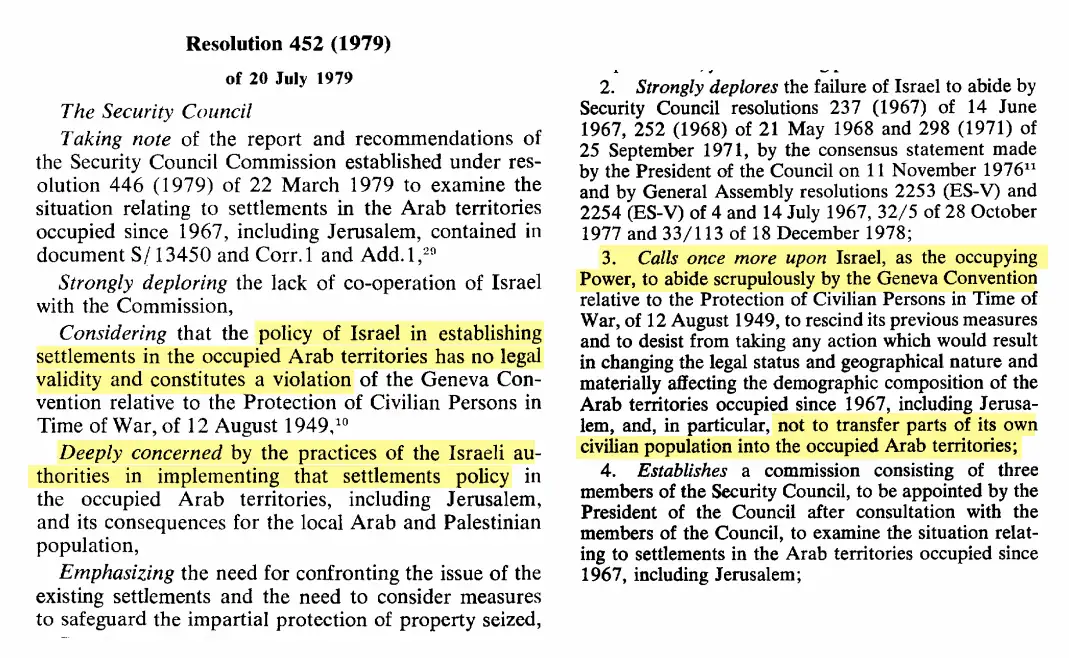

Israel’s actions on a rather shaky internal legal basis continued to be the subject of intense external criticism. Six UN Security Council resolutions (446, 452, 465, 471, 476, 478) in 1979-80, in the absence of a U.S. veto, were quite unequivocal about the legality of what was going on. The settlement issue has been a major point of contention in U.S.-Israeli relations for decades.

Over three decades, with the backing of various governments, 146 settlements were established, and the Jewish population in the West Bank surpassed 100,000.

1992-2023 Third wave: outposts

Since the 1990s, the state’s “honeymoon” with the settlement movement has begun to show cracks. The Rabin government imposed a construction freeze in 1992, partly due to the ongoing peace process with the Palestinians. During the first Netanyahu government (1996-99) and the subsequent administrations of Barak (1999-2001), Sharon (2001-2006), and Olmert (2006-2009), there was a noticeable shift towards a more cautious and restrictive stance on establishing new settlements, influenced by peace negotiations and external pressures.

When the state, if not entirely dismissive, at least turned a blind eye to the settlers, a new tactic emerged — one that continues to this day. Settlement outposts (maahaz) began to be established without any state approval or oversight, making them illegal even under Israeli law and previously accepted norms.

Outposts spring up in various forms — makeshift dwellings, yeshivas, farms — and await retroactive legalization by the state if fortunate, or face demolition and evacuation if not. As governments deliberated on how to handle these outposts, the struggle over each became increasingly charged and politicized.

In 2003, the State Comptroller’s report on the Ministry of Construction, followed by a special report from Talia Sasson in 2005, revealed that despite governmental opposition to illegal outposts, some state and even government agencies continued to offer various forms of support to settlers, including financial assistance.

The establishment of unauthorized outposts undermines standard procedures and rules of good governance, representing a persistent and blatant breach of the law. Public authorities often adopt conflicting stances—at times endorsing and at other times opposing the same practice. The rules have become increasingly flexible, with one hand facilitating the construction of outposts while the other invests resources in their evacuation. These actions involve not just individuals but also state and public bodies, which have participated in violating state law by financing construction without political approval, flouting government regulations, and sometimes even encroaching on private Palestinian property or land not designated for settlement.

From Talia Sasson’s report

That is when another pattern, so familiar to us today, began to develop. Those who questioned or criticized the settlement movement often faced delegitimization and harassment. For instance, Talia Sasson became a “traitor” over time , and the findings of her report, as a professional in the State Attorney’s office, were delegitimized under the pretext of “left-wing” bias. The same fate has befallen a number of human rights organizations that for decades have scrutinized Israeli settlements, their legality and wrongdoing.

In Netanyahu’s second government (2009-2012), amidst the Bar-Ilan speech, dwindling hopes for reviving the peace process, and pressure from the U.S. administration, the approach to settlements was more ambivalent.

However, 2012 marked a significant policy shift. The government not only intensified efforts to expand existing settlements but also began to play along and give the green light to the outpost movement, actively seeking ways to legalize existing outposts, including those built on private Palestinian land.

Since then, a repetitive cycle has unfolded involving settlers, the government, and the Supreme Court, leading to either the demolition or retroactive legalization of outposts. Although some outposts on private Palestinian land have been dismantled due to Supreme Court orders, many others have been either retroactively legalized or managed to evade legal scrutiny entirely.

The most recent Netanyahu government (2022), however, has already violated one of the basic principles of the Israeli domestic legal framework for settlement activity.

Under the coalition agreements, Bezalel Smotrich was appointed as a special minister in the Defense Ministry, overseeing the government coordinator for the controlled territories and the army’s civil administration. In May 2024, Smotrich appointed a close associate to the new position of deputy chief for civil affairs. This shift effectively transferred the authority for managing civilian affairs in the West Bank, including construction issues, from military officers to politicians and civilians. This, of course, has not gone unnoticed abroad, including the current court ruling.

Smotrich openly advocates the abolition of the Palestinian Authority, the annexation of the entire West Bank without extending citizenship to the Arab population, and the repopulation of the Gaza Strip.

98 outposts were established from 1991 to 2005, 132 from 2012 to 2024, 109 of which were established in the last 6 years, 44 – in 2023-24 alone.

according to Peace Now data

1967-2023 Summary

Let’s summarize the situation. After 1967, Israel effectively adopted the principle of occupation and military control over the territories without formally declaring them as its own, except for East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Despite efforts to frame these areas as “disputed” rather than “occupied,” Israel’s imposition of military administration and reliance on interpretations of international law related to occupation have led it into a complex legal position.

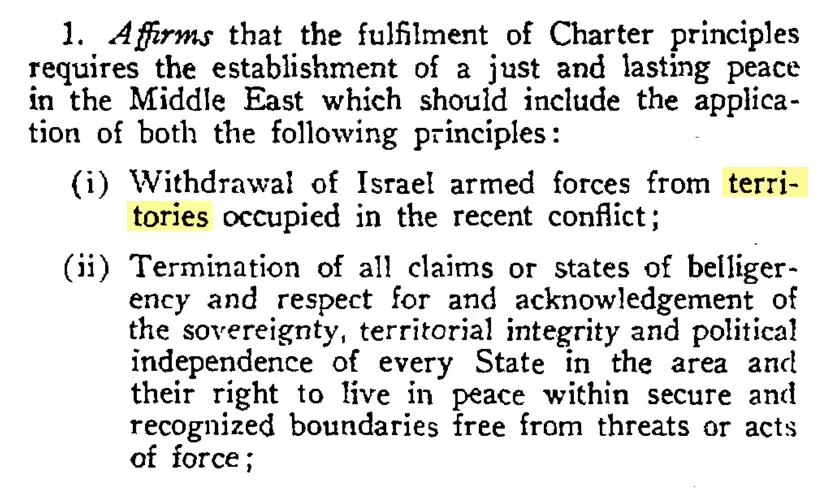

Israel also accepts the principles outlined in UNSC Resolution 242, which call for a future exchange of occupied territories for peace and the resolution of all claims against Israel.

Indeed, a key diplomatic achievement for Israel was that the final wording of the Resolution referred to “territories” rather than specifying whether it meant all the territories.

Nonetheless, Israel has acknowledged that, if genuine peace prospects arise, it is likely that most of the territories will need to be relinquished, as seen with the return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt. Israel has never formally renounced the principles of UNSC Resolution 242, although there have been threats of annexation and a statement by Netanyahu in 2020, amid the Abraham Accords, suggesting a shift towards a “peace for peace” concept, replacing the traditional “land for peace” approach.

Despite this, the state, pretending it has nothing to do with the voluntary settlement movement, has for decades supported and financed it in every possible way, on a basis considered relatively legal only within Israel, while being repeatedly discredited internationally.

The relatively cautious approach of military interests and maintaining an appearance of temporariness in the first decade gave way in the second to a more blunt establishment of permanent settlements on supposedly state lands.

As settlements became more and more contradictory issue in both foreign and domestic policy and the settlement movement gained political power, the state effectively stepped back, choosing not to address the issue directly. However, governments continue to secretly — and eventually openly — support activities that are illegal even by its own standards.

“Temporary” settlements have evolved into towns and neighborhoods with municipal structures that are fully integrated into the state’s governance system. This transformation has occurred without any clear state decision on the matter, leaving open the theoretical possibility that it could all be undone sometime.

Yet, with a population now exceeding half a million, it is clear that the settlers have no intention of leaving whatsoever. They answer the question of whose land their “temporary-permanent” are standing on without any hesitation. This is what the international court justifiably calls an undeclared annexation of territory – an annexation de facto, something that the official Israeli narrative until recently at least tried to deny.

It’s worth mentioning that so far, the international community has condemned only Israel’s actions in the territories under its military control, not the fact of a military presence itself, which is driven by legitimate security concerns and threats of terrorism. No one has seriously demanded that Israel immediately and unconditionally withdraw from these territories, though the tone of recent court rulings has grown more impatient.

What is under scrutiny is not Israel’s need to maintain military control due to a lack of political alternatives, but rather its actions, inconsistent policies, and hidden intentions.

For decades, the world has maintained a consistent stance on Israeli settlements. Meanwhile, Israel has been saying one thing, thinking another, and doing something entirely different.

Was there an expectation that the world would trust our declarations regardless of our actions? Or that the international community would be content with mere condemnations and threats with no actual countermeasures? Perhaps there was a belief that our diplomatic relationships with key partners would shield us from serious repercussions or that global attention would remain elsewhere. As the past year has shown, any such assumptions were precarious at best, and patience for our ever-shifting behavior is wearing thin.

Before jumping to conclusions and addressing the core question of what the Israeli settlements are, let’s first examine another significant aspect.

What does military control mean?

For a truly deep understanding of this topic, we must recognize that Israel’s military control over a vast territory with a large population for nearly 60 years extends well beyond theoretical debates about land status, settlement construction, and the legal disputes over their legitimacy.

Where theory meets practice, even a small zoom-in reveals that behind the heavy curtain of broad, overarching, and nebulous concepts like security—which can conveniently obscure all the gray areas—people’s lives are often what’s hidden. The easiest path is to lock ourselves into this ‘security mindset,’ ignore the issues behind it, and turn a blind eye. But we can also choose to understand what it really means—by listening to what the other side is saying, what the world is saying, what Israeli human rights organizations are saying, and what we persistently try not to hear.

Let us delve deeper into the two primary conflicts that have shaped life in the occupied territories from 1967 to the present: the interactions between the civilian population and the military, and between two groups of civilians.

Civilian clashes with the army

For the first 30 years, nearly all aspects of Palestinian life in the controlled territories depended on Israeli soldiers or officers who, justifiably or not, viewed them primarily as a hostile population. There is nothing surprising or unnatural about this dynamic. The army’s role is not to care for another population, no matter how moral or humane it may strive to be. Its purpose is enforced control.

The next 30 years, up until today, have been shaped by the interim-permanent reality established by the Oslo Accords. Although these agreements granted Palestinians some autonomy in their daily lives and reduced direct interaction with the Israeli military in major cities, this autonomy remains significantly limited, ending wherever and whenever the Israeli army decides.

But what does it mean to be dependent on the army? It means that the laws governing your life are issued as military decrees by an authority you neither chose nor can change or challenge—an authority not intended to ensure the success and prosperity of your society, but whose sole and inherent motivation is to maintain order.

For failing to comply with these decrees, you are tried in a military court, often not in your own language, with translation that may be less than perfect. In the first instance of this court, only one of the three officers is required to be a lawyer. As those familiar with this system often acknowledge, justice and fairness have not always been the top priorities in a military court, unlike in a civilian one.

One of the most widely condemned practices to this day is administrative detention—the ability to detain individuals indefinitely without formal charges, trial, or due process, based solely on suspicion, often supported by classified security evidence, that the person may pose a threat or be involved in illegal activities.

Moreover, the rules governing arrests and interrogations by the Israeli Security Agency (Shin Bet) were not formally regulated until the late 1980s. In 1987, a special commission led by Supreme Court Justice Moshe Landau revealed severe cases of inhumane treatment and brutal torture of detainees, which had previously been systematically denied by Shin Bet personnel.

Needless to say, as terrorist threats have intensified over the decades, approaches have become more ruthless, and tolerance for perceived risks has been effectively reduced to zero.

It must be admitted that many of these decisions indeed presented profound moral and ethical dilemmas, with lives weighing heavily on both sides of the scales. The separation fence and partial restrictions on freedom of movement significantly curtailed the wave of violent suicide attacks during the Second Intifada. However, these measures also infringed upon the rights and daily lives of many Palestinians who were likely not involved in terrorism at all.

It would also be naive to assume that all security measures have always been justified or that military actions have consistently aligned with genuine security needs. Concepts like security, threats, and risks are highly subjective and scalable, subject to broad and varying interpretations. What, after all, constitutes security? And can absolute security for some justify absolute insecurity for others?

Many retired high-ranking internal security officers have acknowledged in various testimonies, including the acclaimed documentary series Shomrei ha-Saf (שומרי הסף), that many mistakes were made along the way and numerous lives were unjustly broken.

In retrospect, the first Coordinators of Civilian Affairs in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Shlomo Gazit in his book Trapped Fools and Yitzhak Ini Abadi in his interviews, also reassess the questionable state actions and military decrees.

It is through military decrees that locals often discovered the confiscation of their lands—whether for settlements, military and other infrastructure, the construction of bypass roads, or the building of a barrier. Just imagine for a moment receiving such a decree that you practically cannot even dispute.

In the first decades, relative freedom of movement was maintained. However, the extensive system of roadblocks that developed in 1990-2000 significantly restricted it as well. Not to mention the army’s frequent closures of entire neighborhoods and settlements due to operational activities of varying duration. A most recent and striking example of this occurred after October 7, when Arab residents of the Jewish part of Hebron were subjected to an unofficial curfew for several months, living in fear of leaving their homes at inappropriate times due to the risk of being rudely treated or threatened by soldiers.

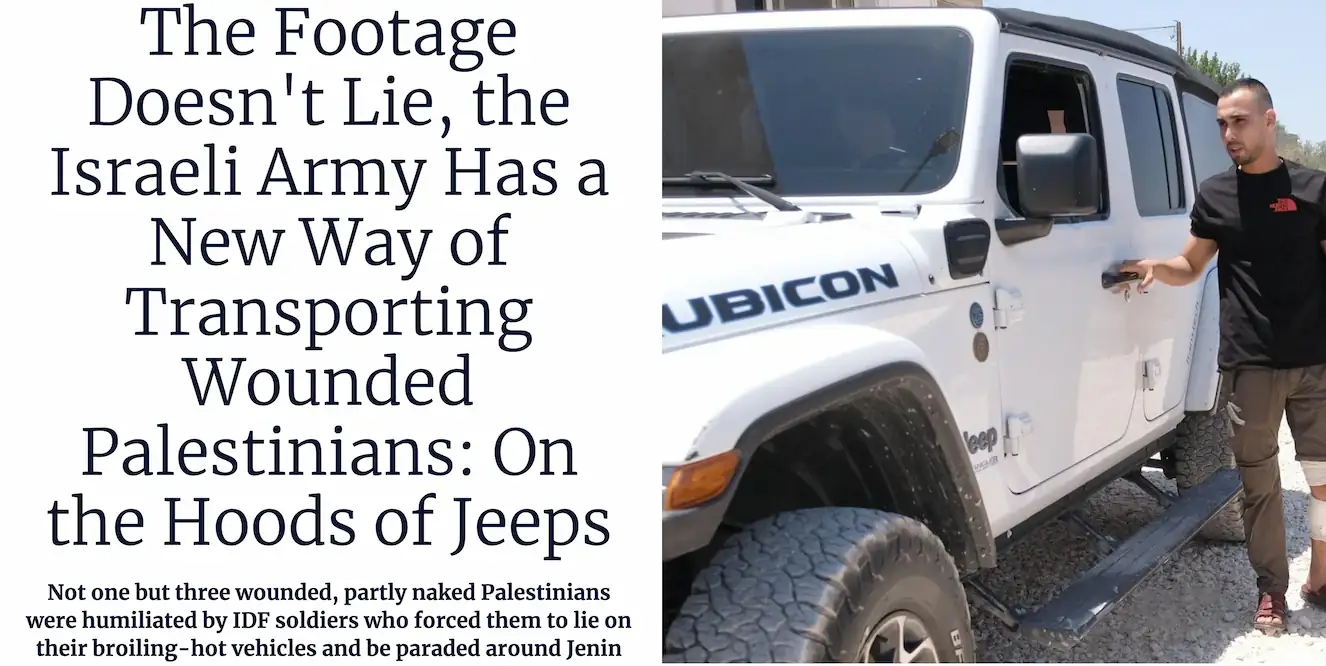

Unfortunately, incidents of unjustified violence by soldiers are also not so rare. Just recently, disturbing footage showed two wounded and beaten Palestinians being forced to ride on the hood of an army jeep under the scorching sun. While we prefer to regard this as an exception, it’s neither the first nor the last case of its kind. For instance, there have been extensive reports of systematic brutality by members of the Netzah Yehuda battalion. One of the most notable cases involved the death of Omar Asad, an 80-year-old Palestinian with American citizenship, which led to the battalion being reassigned to the north.

The human rights organization Yesh Din (יש דין) reports that, according to the army, 1,260 complaints were filed between 2017 and 2021 regarding alleged crimes committed by Israeli soldiers against Palestinians, with 409 of these cases involving murder. However, only 248 criminal investigations were initiated—roughly one-fifth of the total complaints, including 117 murder cases. Of these, only 11 investigations led to indictments, and just three were related to murder. This means that soldiers were held accountable in only 0.87% of the total complaints filed.

Almost every week, the Twilight Zone column in Haaretz brings to light new evidence of violence against Palestinians, perpetrated by both soldiers and radicalized settlers.

The organization Breaking Silence (שוברים שתיקה), founded by soldiers who served in Judea and Samaria, has compiled hundreds of testimonies from these soldiers, sharing their experiences and the events that left them traumatized.

It should be noted that these organizations, along with several others opposing the Israeli presence in the controlled territories, are systematically attacked and devalued—not through valid counter-arguments, but rather through labeling and accusations of attempting to discredit Israel.

Even if one were to doubt the validity of all these recorded incidents, testimonies, reports, and statistics—say if 90% of them were refuted or justified— even the remaining small fraction and the sheer volume accumulated over the decades paint a highly disturbing and bleak picture for the rule of law. This alone warrants serious public and political attention.

Moreover, within Israeli society and among political leaders, there is a growing erosion of accountability and legal oversight for military personnel. Take, for instance, the case of Elor Azaria, who openly disregarded the rules of engagement, or the most recent allegations of abuse and torture of prisoners at the Sde Teiman base. Israeli society and the political echelon are seriously debating whether Israeli soldiers who apparently violate the country’s laws should be investigated and tried at all.

Either way, very few of these cases make it to the mainstream Israeli media. This explains why such incidents remain relatively unknown to the public and why each case that does surface often seems surprising as some sort of another unfortunate exception rather than part of a broader pattern.

Alongside intentional violence, military operations often result in numerous injuries and deaths among the civilian population, whether through mistaken actions or as a consequence of operational needs. Yet, it is important to remember that what is “collateral damage” or a “unfortunate mistake” for the security system is also a shattered world and a tragedy for countless families.

Clashes between two civilian groups

Alongside frequent interactions with the Israeli army, the Arab population inevitably faces encounters with settlers. Most of them are peaceful individuals who choose to live where they live due to personal beliefs or other reasons. To a large extent, Israeli society views these settlements on the ‘state’ land and their residents as ordinary citizens of the state, who certainly do not seek violence.

However, this is not how the Arab population views the situation. For decades, Palestinians have witnessed the steady expansion of Israeli construction on what they consider, no matter rightly or wrongly, to be their land. They have seen small tents in the hills evolve into a series of structures, then into full-fledged settlements with beautiful signage and paved roads.

Meanwhile, a political resolution to a war that ended nearly 60 years ago seems ever more distant and elusive. One can indeed argue that the blame for the insolubility of this conflict so far rests as much and maybe even more with Palestinians and their leadership. And that is a whole another matter for debate. But if we are talking about daily reality and how ordinary Palestinians view it, then the reality for them is this – military orders and growing settlements.

If only the daily routine for the Arab population in the West Bank ended there, having to deal solely with the Israeli army and peaceful settlers. But the reality is far more grim and complex.

The issue of settler violence is not new. It came about in 1970s and has been evolving ever since. Precisely at that time Shin Bet enabled a special, so-called “Jewish Department” that worked to prevent numerous Jewish terrorist attacks, including attempts to blow up the Temple Mount.

In the early 1980s, Miriam Karp of the Justice Ministry was tasked by the Israeli government to prepare a report on Jewish terror activities against Arabs in the West Bank. The report’s key findings, regrettably, remain strikingly relevant today: uneven policing, inadequate investigation and prosecution, underreporting of incidents, prevailing bias and lack of accountability.

According to the Yesh Din organization, between 2005 and 2023, 93.7% of investigative cases involving settler violence were closed without indictments. Out of 1,664 investigations into violence by Israeli civilians against Palestinians in the West Bank, charges were filed in only 107 cases (6.6%). Report also claims that police have not adequately handled 81% of those investigations. Again, if out of this number we consider substantial, say, just a third, we still get a profoundly troubling figure.

The Israeli public has been exposed to only a few of the most blatant cases of settler violence. Among the most notorious are Baruch Goldstein’s shooting of 29 worshipers at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron in 1994, the arson attack and murder of a family in the village of Duma in 2015, the recent pogrom in the village of Hawara in 2023, the latest assault on Jit village, and other attacks in the “Price Tag” series of revenge and lynching acts.

However, the ongoing, almost daily stream of smaller incidents of unjustified violence and terror is largely overlooked, rarely condemned, and, worst of all, remains virtually unpunished.

Jewish radicalism is often dismissed or downplayed as merely the actions of a violent minority that doesn’t represent the broader settlement movement. However, this response falls short of condemning or challenging the issue and avoids addressing the obvious questions: Where does this radicalism originate? Who is fostering and inspiring it? And most importantly, how can it be effectively combated and eradicated?

Furthermore, Israeli society and the media, whether consciously or not, whitewash this phenomenon by avoiding calling it by its proper name. Any violence by Arabs is automatically labeled as terrorism, and the perpetrator is called a terrorist. On the contrary, when Jews commit similar acts, they are rarely framed as terrorism, leading to a double standard in how violence is portrayed and addressed.

Under-prosecuted settler violence deepens an already troubling reality, exposing two fundamentally different justice systems operating within the same territory. While Arab violence is pursued to the fullest extent of the law, Arab victims of Jewish violence find it nearly impossible to seek protection or justice from Israeli authorities. This atmosphere of lawlessness in the West Bank is precisely what critics refer to when describing Israel as an apartheid state, rather than the situation inside the Green Line, as some falsely perceive.

Yet Israel continues to overlook this flawed enforcement system and proudly presents itself as the sole democracy in the Middle East, governed by the rule of law.

Let’s summarize our extensive yet somewhat superficial exploration of what living under military rule means. Since the 1990s, if you live in major West Bank cities designated as Areas A, work and spend most of your time there, your interactions with the Israeli army are generally limited to occasional operations in your city. If you’re fortunate enough not to be near any terror infrastructure or come under fire by accident, you might avoid the worst of the outcome.

However, if you reside in Areas B or C, navigate between them, or work in Israel, friction with the army and settlers becomes almost inevitable. In these cases, you might face intentional violence or unintentional abuse of power, that you probably won’t be able to seek justice for, and safely navigating this reality can be profoundly difficult.

This is not to mention the decades of total political uncertainty and the inability to exercise civil rights or pursue any national aspirations.

So what are settlements?

The issue of settlements and Israeli policy in the West Bank often triggers a backlash that shifts the focus to Palestinian violence and the challenges of resolving the conflict under current conditions. This, in fact, serves as a perfect way to avoid answering the hard questions. But let us play along, entertain this perspective and examine settlements not as an isolated policy, but within the broader context of the conflict and the peace process.

Are settlements and Israeli policies in the West Bank the main obstacles to peace? Clearly not. The peace process encounters greater challenges, including ongoing Palestinian radicalism, the goal of dismantling the Jewish state, and the lack of political cohesion within Palestinian society.

Are settlements and Israeli policies in the West Bank an obstacle to peace in generall? Depends on one’s point of view.

For those who believe that the solution to the conflict lies in the suppression and defeat of one people by another, settlements and annexation are seen as necessary steps rather than obstacles.

Those who believe that the only viable solution for two warring peoples on the same land is to establish two separate states (not insisting that this must happen immediately) argue that settlements significantly complicate any potential future peace agreement, if and when the Palestinian side overcomes its major obstacles and the Jewish side does not abandon the two-state principle in the meantime.

It is also impossible to ignore the impact of military presence and settlement policies on the course and nature of the conflict. True, the hypothetical removal of the settlements from the equation today does not automatically guarantee peace. Yet it is undeniable that settlements constitute a clear poke in the eye for Palestinians. Furthermore, we cannot really know how Palestinian-Israeli relations might have evolved without settlements in place.

Was there another way whatsoever? The answer is both yes and no.

In practice, Israel could not have annexed the territory without offering citizenship to the substantial Arab population, which would have jeopardized the Jewish majority within its borders. Could Israel have declared the territory its own without extending citizenship? According to international law, clearly not. However, the big question is what diplomatic repercussions Israel might have faced if it had done so, say, right after the war in ’67. Could Israel have negotiated the return of the territory to Jordan on more favorable terms than those proposed in the Alon Plan? Or could it have opted to halt settlement expansion and maintain the area under exclusive military control?

We can only speculate about where those options might have led, but different paths are always available – it is just a matter of choice. Obviously it’s always easier to contemplate in retrospect. Each bold option required thorough strategic analysis and honest consideration of where our current policy might lead us in 10, 20, or 50 years.

And so, ultimately, what settlements represent is nearly 60 years of no strategic decisions whatsoever, and a lack of clear direction or long-term vision. It is a series of thousand tactical steps, without much understanding in which direction.

Without a doubt, the situation Israel has faced since the founding of the state is extraordinarily complex and historically unprecedented. There are no straightforward or clear-cut solutions, and every potential path carries significant risks and the possibility of grave consequences.

However, if our strategy is a no-strategy—if we systematically avoid making decisions and simply go with the flow—we must also be prepared for the situation to potentially get out of control. While the full extent of the problem might not have been evident in 1967, nearly 60 years later, it is clear that under the disguise of routine stability, our unresolved issues are becoming increasingly severe, complex, and dangerously volatile.

So, one can only guess at the total cost of the ever-growing bill we will face for this ongoing stagnation. Perhaps it would be wise to pause and consider the consequences of continuing to evade answers and neglecting to address that same question: where our current policy might lead us in 10, 20, or 50 years.

However, the problem cannot be attributed to politicians alone; it also reflects issues within society. Many crucial topics have been pushed off the agenda and have practically become taboo in recent decades.

The fact that discussions about the conflict in general, and settlements in particular, have become a minefield for ideas where any expressed opinion leads to labeling, harassment, and discrediting, indicates either immaturity or unhealthiness in our society. If any of the ideas presented here made you uneasy, it only highlights how the topic has been severely manipulated to the point where it can no longer tolerate dissenting views.

The ostracism and prejudice faced by various watchdog organizations and media outlets for merely reporting uncomfortable truths and challenging official narratives underscore a departure from genuine pluralism. This suppression of dissenting voices suggests that true diversity of thought has been left behind.

In our pursuit of complacency and supposed moral superiority, we’ve almost lost the ability to critically assess our actions and ask ourselves the essential question: is what we’re doing truly right? Instead, we find numerous ways to dodge the conversation, change the subject, or respond with manipulative deflections.

We have settled into a routine where we avoid discussing any broader strategy or future aspirations. Instead, our focus has shifted to daily survival tactics, with a blind hope that tomorrow will be just as uneventful as today—free from explosions, tragedies, and destruction.

We are both witnesses and accomplices to the decline and narrow-mindedness that have overtaken political discourse within our society.

Meanwhile, the state, or at least some of its representatives, whether we agree to it or not, pursue policies that are at times concealed, at times blatantly overt, yet rarely subject to public dispute. It often seems that we neither know nor truly want to know what is being done in our name.

But ignorance, as we are well aware, excuses no one and the bill is always handed to the public.

Share