This week, two events reminded Israeli society of the so-called Parashat ha-Tsolelot – the Submarine Affair.

Former Israeli navy commander Eliezer ‘Chiney’ Marom was unexpectedly appointed coordinator for the reconstruction of settlements on the northern border. Until 2021, he was also the main suspect in Case 3000, a corruption case involving the Israeli army’s purchase of warships and submarines from the German company ThyssenKrupp.

The second development was the publication by the state commission investigating the case of preliminary findings and warning letters to several key figures, including Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, former Mossad head Yossi Cohen, and former Chief of General Staff and Defence Minister Moshe ‘Bogie’ Ya’alon.

We have studied many documents and evidence, checked several versions, and gathered everything you need to know about this case. Let’s dive in and look at how corruption, interests, and negligence infiltrated the “holy of holies” of modern Israel and why this is so relevant today.

* Ranks in the text are given at the time of the events described

Background

Israel initiated its submarine purchases in the 1960s, but the modernization of its fleet with contemporary submarines began in the early 1990s.

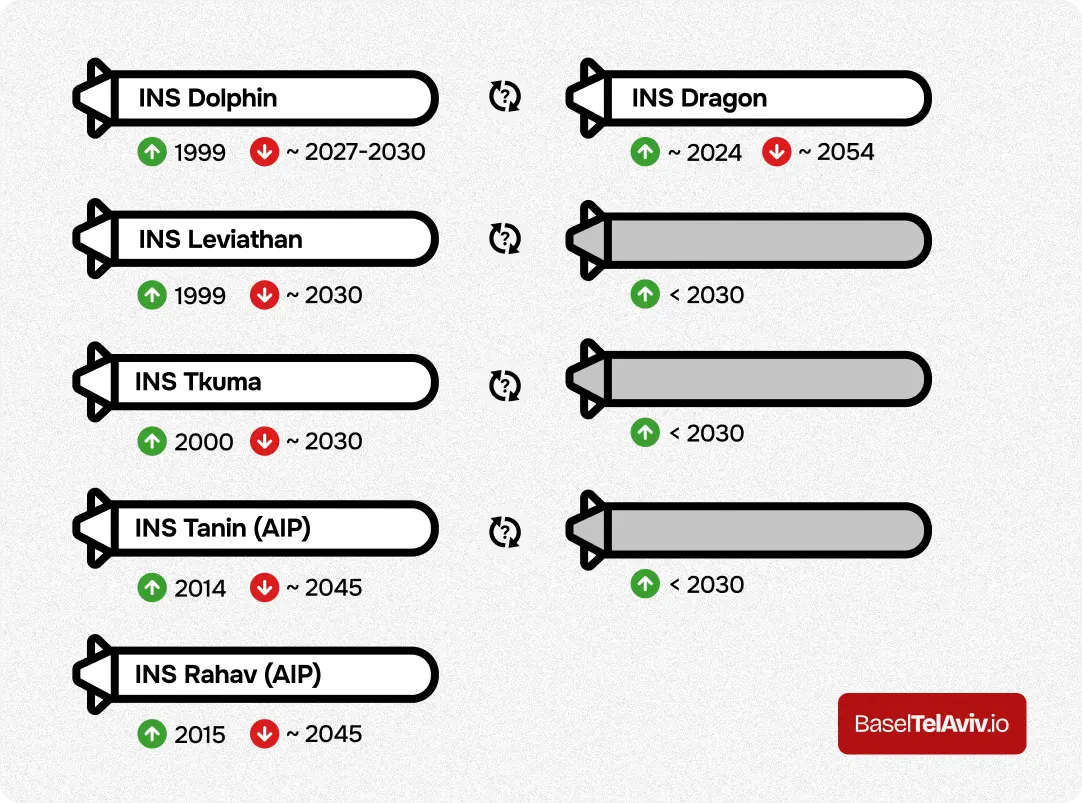

By 2009, Israel already had three submarines in service (unofficially, at least one of them a nuclear weapons carrier). The three subs were delivered to Israel between 1997 and 2000. Around that time, Israel ordered two more subs, entering service in 2014 and 2016.

The acquisition of all five modern submarines, produced by the German company ThyssenKrupp, underscored the special relationship between Germany and Israel, highlighting Germany’s substantial support for the Israeli defense sector.

The first two of the five subs were fully funded by Germany against the backdrop of the 1991 Gulf War, during which Saddam Hussein’s Iraq fired ballistic missiles at Israel. Germany funded the third boat by half, the fourth, and the fifth by a third.

Submarines are the most expensive weapon in the Israeli army to manufacture and maintain. According to some estimates, the total cost of procuring, equipping, and maintaining a single submarine for its entire life cycle can be as much as 25 billion shekels. By comparison, this is almost half of Israel’s annual defense budget (until 2023).

According to numerous army and defense experts, five submarines are the optimal flotilla size for Israel in terms of operational and strategic missions and economic viability. The submarines are estimated to serve about 30 years before decommissioning, so the first three submarines are initially estimated to be replaced in 2027 and 2030, the fourth and fifth around 2045.

What’s behind the submarine affair?

The Submarine Affair, or Case 3000, was born out of a journalistic investigation by Raviv Drucker in 2016. The case is based on a series of significant events from 2009 to 2016.

Following the transition from the Olmert to the Netanyahu government in 2009, numerous government officials and private individuals actively promoted deals with ThyssenKrupp through the Prime Minister’s Office and the National Security Council. They significantly influenced some of the Israeli defense sector’s most critical and costly decisions.

Let’s break down each of them separately.

The purchase of a sixth submarine

Contrary to the official opinion of the army, the Navy, and personally the Chief of General Staff (2007-2011) Gabi Ashkenazi, between 2009 and 2012, a decision was taken to buy a sixth submarine at a cost of about 500 million euros. At that time, the Navy clearly and explicitly stated that they had other, more urgent priorities, namely the renewal of the missile boats.

The Chief of Staff also warned that not only the Navy but the army, in general, had more urgent priorities: “If we spend money on a submarine, we won’t even have money for an APC for Golani soldiers in Shuja’iyya” (the infamous neighborhood in the Gaza Strip).

Subsequently, many military officials stressed that the political decision to acquire a sixth submarine appeared highly controversial at best, and they were quite surprised by the significant pressure from the Prime Minister and the National Security Council.

Moreover, eventually, the army estimated that it was neither necessary nor feasible for Israel to maintain six subs, so the delivery of a sixth sub would likely have meant replacing and decommissioning the first sub ahead of schedule by at least a few years.

The debate over the optimal number of submarines existed, as did the opinions of some military experts (e.g., the head of the NSC 2011-2013 Yaakov Amidror), that a sixth submarine would probably not be excessive, at least from the military point of view.

However, economically, maintaining six submarines is a big issue, and years later, various Army and Ministry of Defense documents still maintained that the optimum number of submarines had stayed the same. So, it was likely that the first submarine would be written off early when the sixth submarine was delivered.

Nonetheless, the production of the submarine has been severely delayed, and it is not expected to be delivered until this year.

Procurement of four corvette-class ships

In 2010, the significant Leviathan gas field was discovered 120 kilometers from the Israeli coastline. As part of the concession agreements, the IDF was tasked with providing security for the production platform. This obligation conveniently justified the Navy’s renewal of its fleet at the time.

The military assessed the ships necessary for this task, and the government approved a plan to acquire four vessels with a displacement of 1200 tons, allocating a budget of $400 million.

Israel was in negotiations with South Korea, a recognized leader in this segment according to experts, for the potential purchase of ships. These negotiations were intergovernmental, and Korea reportedly offered to include the technology of the successfully tested Iron Dome system along with a favorable pricing proposal.

Simultaneously, the Ministry of Defense issued an international tender that attracted participation from seven companies, including Israeli ones. Even before the tender was announced, the Prime Minister’s Office and the National Security Council pressured the ministry to abandon it. Later on, due to this pressure, the tender was effectively canceled, and the decision was made to order the ships from the same ThyssenKrupp company under the strange pretext that there was no point in the tender because the German company was the best possible supplier.

The justification was the strategic relationship with Germany and the significant discount they allegedly offered. Still, some officials never understood what prevented the German company from winning the tender if that was the case. In 2019, Shmuel Zucker, head of the Defense Ministry’s procurement department, revealed that he faced much pressure at the time, including threats, suggesting that refusing to cancel the tender would harm Israeli-German relations and that he would be held responsible for any fallout.

Another issue was that ThyssenKrupp was constructing larger ships than Israel required, based on the government’s assessment of the army’s needs. Consequently, the defense establishment significantly altered the technical specifications for the vessels, leading to the order of larger corvettes with a 2000-ton displacement. This change necessitated additional budgets and caused delays in project deliveries.

Additionally, it soon became apparent that only a temporary drilling platform was located 120 kilometers away, whereas the army had eventually ordered the main rig to be situated just 10 kilometers from the Israeli coast, which wouldn’t justify such an upgrade in the first place.

Either way, the four corvettes represented a significant upgrade for the Israeli Navy. However, the supplier selection process had already raised substantial questions among defense officials at the time.

An attempt to privatize a military shipyard

In 2016, the same officials and private individuals started advocating for partially privatizing the military shipyard responsible for servicing Israeli Navy vessels. They argued that the shipyard might be unable to maintain the newly acquired ships and suggested that ThyssenKrupp should take over their maintenance instead.

Even Navy Commander Ram Rothberg endorsed the privatization idea at the time. However, the Ministry of Defense and the General Staff were again caught off guard by such plans and raised objections. They emphasized, though, that any privatization of the Navy’s facilities should follow a formal tender process rather than simply transferring rights to a German company.

The decision was based on insufficient analysis, evidence, and arguments to show that the shipyard operated inefficiently. The justification, as later revealed, stemmed from an artificially created labor dispute that resulted in two months of downtime.

The privatization process was halted following the publication of an investigation into the matter.

Between 2009 and 2016, several more suspicious processes unfolded, during which the Prime Minister’s Office and the National Security Council frequently bypassed the Ministry of Defense and the IDF General Staff in strategic decisions regarding the re-equipping of the Marine Corps.

Ordering three more submarines

According to National Security Council head Yaakov Nagel, in August 2015, Prime Minister Netanyahu ordered the consideration of expanding the fleet by contracting for three more submarines. This decision bypassed the General Staff and Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon, who claimed he was unaware of such an intention.

All this occurred against the backdrop of the State Comptroller’s reports highlighting acute shortages and budgetary problems within the army. The sudden intention to expand the fleet to nine submarines, especially when the order for a sixth one was already in doubt, caused bewilderment and fierce opposition from the entire defense establishment. Subsequently, the narrative changed, suggesting that the plan was not to acquire additional ones but to replace three submarines that had been put into service between 1997 and 2000.

This prompted a valid question from the army leadership: why enter a vastly expensive contract to replace the subs in 2016 when they were still 11 to 14 years away from the end of their service life?

In response, the Prime Minister argued that this was a unique opportunity to purchase the submarines at a favorable price, facilitated by a special relationship with German Chancellor Angela Merkel. However, the defense establishment firmly refused to proceed with the deal at that time. They insisted on obtaining an official guarantee or option to buy the submarines at a reasonable price when the actual need arose.

Officials in Israel and Germany argued at the time that German-Israeli relations were not particularly threatened, and there was little reason to believe that the defense arrangements could have been severely renegotiated even if a less pro-Israeli politician had come to power in Germany.

Eventually, the Prime Minister and the National Security Council made an independent decision and did sign a purchase agreement. However, the deal was frozen following the publication of the case and the start of a police investigation.

The new contract for the purchase of three new-design (Dakar) submarines, with a total value of 3 billion euros, was signed in 2022. The first of the three vessels should be ready by 2030.

At the same time as purchasing the three additional submarines, the Prime Minister also agreed with Germany to purchase two anti-submarine ships. This decision angered and confused the defense establishment, as the order did not originate from them, and there was no indication that Israel needed such vessels. It was unclear what kind of submarines Israel intended to counter. This purchase was also frozen pending further realization. However, the reasons behind Israel’s potential need for such ships began to emerge around that time.

Israel’s consent to the sale of submarines to Egypt

Germany first asked Israel to approve the sale of submarines to Egypt back in 2007 and was turned down by Prime Minister Olmert. The following request came in 2009 after the new Netanyahu government took office. Extensive discussions ensued, leading Israel to conclude that it was preferable to agree and supervise the process with Germany rather than risk Egypt seeking submarines from alternative suppliers. Eventually, Israel agreed to sell less advanced submarines while retaining control over the supplied technology.

Following the revolution in Egypt in 2011 and the brief rise of Islamists to power, Israel reevaluated its stance. In political-military cabinet discussions, there was consensus that even after Egypt stabilized with the arrival of a new president in 2014, the sale of more advanced weaponry could not be further approved.

However, during a 2015 visit to Germany, Amos Gilad, head of the Defense Ministry’s political-military department, was stunned by German colleagues’ claims that Israel had authorized the sale of two advanced submarines to Egypt.

Gilad approached Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon, who was equally surprised by this revelation. Ya’alon then consulted with the Prime Minister, who strongly denied granting any such consent. Following this, Ya’alon asked the country’s president to verify with Merkel during her visit to Germany to confirm the accuracy of the information, resulting in a highly awkward situation. According to reports, Merkel was surprised and allegedly asked President Rivlin if he even knew what was going on in his country.

In 2019, Netanyahu admitted in an interview on Channel 12 that he did approve the sale without informing anyone, claiming, “there are some secrets that only the prime minister can know.” This explanation, along with the Prime Minister making the decision alone without holding any discussion or official approval while concealing this information, further infuriated Israel’s military and political leadership.

Worth mentioning that similar circumstances occurred during the signing of the Abrahamic Accords in 2020, when it was revealed that the prime minister had authorized the sale of U.S. fighter jets to the UAE without informing the defense establishment.

In the uncovered corruption case, evidence suggests that it’s also a lobbying from ThyssenKrupp’s representative in Israel that influenced the approval of Israel’s sale of subs to Egypt. So, who are the suspects in the case?

The suspects in the case

As previously mentioned, Drucker’s publication exposed these processes and triggered a police investigation. It was revealed that several individuals were aggressively advancing the interests of the German company.

Miki Ganor, appointed as the company’s official representative in Israel in 2009, received substantial bonuses for his deals. He accumulated approximately 10 million euros from two transactions involving the purchase of a submarine and four corvettes. Additional pending deals could have brought him tens of millions more. Ganor is the primary suspect in the corruption case, who was allegedly bribing the other suspects. Initially, he agreed to cooperate with the prosecutor’s office as a state witness but later retracted his testimony, reinstating the original charges against him.

David Shimron, a lawyer and counselor who is a cousin and close confidant of Prime Minister Netanyahu, was hired by Ganor to represent ThyssenKrupp’s interests. Shimron played a significant role in promoting nearly all of the mentioned deals. At times, he acted as Ganor’s or the German company’s representative, but more often, he performed as a close advisor to the prime minister. So, many witnesses claim they were mostly unaware of Shimron’s ties to Ganor and ThyssenKrupp during these dealings.

The prosecutor’s office dropped the initial bribery charges against Shimron and pursued only a money laundering charge. It concluded that while Shimron was on a salary and did not receive bonuses from deals, he aided Ganor in illicit money transfers.

Avriel Bar-Yosef. As deputy head of the National Security Council, he actively promoted all the deals. The prosecutor’s office alleges that Bar-Yosef colluded with Ganor and requested a bribe of several million euros after resigning. It is also believed that part of the intended bribe money was transferred to another individual implicated in the case.

Eliezer ‘Chiney’ Marom, former commander of the Navy, faced suspicions of accepting bribes during his tenure. According to the initial case file, Marom significantly influenced the German company’s decision to replace its previous agent with Miki Ganor. After retiring from the Navy, Marom joined Ganor as an advisor and received over 500,000 shekels for his services.

Marom has argued that his employment was based solely on his decades of naval experience and was unrelated to Ganor’s promotions as an agent. He claimed personal opposition to the purchase of the sixth submarine as evidence. However, conflicting witness testimonies in the case imply that it was not so obvious and suggest Marom’s involvement in discussions regarding the privatization of the shipyard.

Ultimately, charges against Marom were dropped following the discovery of new evidence: a recorded conversation between Ganor and another party before the investigation began, where Ganor admitted that no prior contract with Marom existed.

In Asaf Lieberman’s Zman Emet program (זמן אמת) on כאן 11, when asked if it was correct in principle that Marom went to work as an advisor to a man whose appointment he promoted while in a high position in the army, Marom replied that he saw nothing wrong with it.

The prosecutor’s office also implicated David Sharan, head of the Prime Minister’s Office, who received NIS 129,000 from Ganor, and former minister and Keren ha-Yesod chairman Modi Zanberg, who received NIS 103,000, among several other individuals in the case.

Role of the Prime Minister

There has been considerable suspicion surrounding Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s involvement in Case 3000. Despite significant public pressure on the government’s legal advisor and Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit, he decided that no further investigation was needed and dropped suspicions against the Prime Minister. Netanyahu asserted that his actions were guided solely by national interests, particularly in light of the Iranian nuclear threat and his commitment to fostering relations with Germany.

In 2018, it was revealed that costs related to other legal cases against Netanyahu were partially covered by his cousin, American businessman Nathan Milikowski. This revelation drew the attention of State Comptroller Yosef Chaim Shapira, whose inspection brought new details to light.

In 2007, Netanyahu purchased shares of Milikowski’s SeaDrift Coke for $600,000 and sold them to his brother in 2010 for $4.3 million. According to the State Comptroller, there were no records of these transactions in his office. The significant 700% gain in just three years on shares of a company owned by Netanyahu’s relative, which was reportedly unprofitable at the time, raised numerous questions. Allegedly, the shares were initially offered to Netanyahu at a substantial discount.

The secretive nature of these share transactions between a top politician and his cousin’s company raises suspicions of potential illegal gifts and financial irregularities. Moreover, Netanyahu’s cousin regained these shares just before SeaDrift Coke merged with Graftech, making Milikowski a major shareholder (11.2%) and board member in the merged company.

Graftech, in turn, is a significant supplier to ThyssenKrupp, a company whose procurement decisions were on the prime minister’s agenda at the time. Even though Netanyahu sold the shares, his cousin’s subsequent involvement as a shareholder in a supplier to ThyssenKrupp raises concerns about possible conflicts of interest.

However, Avihai Mandelblit, despite receiving these materials, chose not to pursue investigations into any of these issues. Regarding potential financial fraud, he cited the expired statute of limitations on the case. Concerning the submarine case, Mandelblit stated, “there are significant gaps to build a criminal case that cannot be filled with speculation, conjecture, and general inferences.” In essence, he indicated there was insufficient direct evidence to suggest that Netanyahu may have been influenced by external interests.

Mandelblit’s decision not to delve deeper into so many coincidences and conflicts of interest appeared, at best, questionable.

State Commission of Inquiry

The details of the submarine affair sparked public outrage on multiple fronts. Firstly, the criminal implications were staggering, revealing corruption schemes surrounding crucial security purchases.

Additionally, serious questions arose about the decision-making process at the highest levels of government. How could there be such a disconnect in politico-military coordination, with politicians overriding professional military advice and proceeding with significant security deals without proper consultation?

Until Netanyahu’s 2019 interview, the sale of submarines to Egypt remained shrouded in mystery, with the prime minister consistently denying involvement and attributing decisions to independent German actions.

When the truth emerged, Israelis were shocked to learn that decisions to sell strategic weapons to a neighboring country were made without the knowledge of crucial defense officials, including the Defense Minister, IDF Chief of Staff, Navy Commander, heads of intelligence, and other critical positions.

This outrage generated intense public pressure to establish a State Commission of Inquiry. Unlike parliamentary or governmental commissions, a State Commission of Inquiry is seen as the most independent instrument for scrutinizing public authorities. While the government decides to establish it, the commission’s composition and chairperson are appointed by the president of the Supreme Court.

From the outset, the commission’s establishment was heavily politicized by the Prime Minister, who portrayed it as an alleged attempt to undermine his authority. Despite this, the call for a commission was supported not only by clear public demand but also by numerous former and current military personnel directly or indirectly involved in the events.

In 2021, the Movement for Quality of Government collected and presented 50 official testimonies from former defense ministers, chiefs of staff, heads of Mossad, Shin Bet, and Aman, commanders of various military branches, and other senior Israeli security officials. All expressed grave concerns about the decision-making processes and urged thorough investigations into the events spanning 2009 to 2016.

The Benet-Lapid government decided to establish the commission in 2022. Former Supreme Court President Asher Grunis, known for his conservative judicial approach, was appointed the commission’s chairperson.

This week, the commission issued warning letters to several officials: Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, former Mossad head and head of the National Security Council at the time of the events under investigation Yossi Cohen, former Defense Minister Moshe ‘Bogie’ Ya’alon, retired Navy Commander Ram Rothberg, and former National Security Council official Avner Simhoni. These letters indicate that the final findings may adversely affect the individuals named, and they are granted the opportunity to provide testimony that could influence the commission’s recommendations.

The commission has also released interim findings concerning these individuals. Here are some of the most significant ones.

The commission’s conclusions on the PM’s actions

- Made decisions with significant consequences for the country’s security outside due process.

- Negotiated agreements with Germany on a number of security and economic issues without keeping records and bypassing the government.

- Turned the National Security Council into its own executive body, which acted in parallel and in contradiction with the Ministry of Defense, in the areas of responsibility and competence of the ministry.

- Promoted the purchase of a sixth submarine and further expansion of the fleet based on unfounded assumptions, without proper analysis and in strict contradiction to the operational requirements set by the government.

- Avoided discussing the problem presented to him of the impact of a significant budgetary burden on the army’s combat capability in the short and long term.

- Made decisions on critical military and political issues without due consideration and bypassing relevant security services.

- Avoided documenting a number of meetings and appointments to prevent the ability to monitor and track the implementation of decisions that were of strategic importance to the security of the state.

- Created two parallel and contradictory action channels, jeopardizing state security and damaging international relations.

Overall conclusion: Mr. Netanyahu’s conduct in the matters investigated by the commission led to deep and systematic irregularities in the military force-building work processes and decision-making mechanisms on a number of sensitive issues, compromising the security of the state and harming the country’s international relations and economic interests.

Commentary: why is all so important today?

The commission’s preliminary findings, after a thorough investigation and interviews with 160 individuals, have substantiated many claims raised in Drucker’s investigation and petitions from the Movement for Quality of Government, which were previously dismissed by the prime minister and his allies.

Despite this, Netanyahu continues to sidestep direct responses to the case, opting instead to employ populism and demagoguery. He seeks to discredit the commission itself and politicize any scrutiny of its findings:

רה”מ בנימין נתניהו בהתייחסות לוועדת החקירה לפרשת הצוללות: “מוכן לספוג את הנאצות, את ועדות החקירה שלכם למען ביטחון ישראל. שום ועדת חקירה שמונתה ע”י ממשלה קודמת במטרה פוליטית ברורה לא תשנה זאת”@netanyahu pic.twitter.com/LCz18qcGMq

— ערוץ כנסת (@KnessetT) June 24, 2024

“I will not entertain inquiries during a war because now is not the moment for that. But let me be clear: the decisions I made regarding the submarines and naval acquisitions were and remain crucial for Israel’s security against the Iranian threat. The effectiveness of these acquisitions is evident today as those same ships intercept drones aimed at our country and save lives. What would have happened if I hadn’t made those decisions?* You bring up bureaucratic norms, but I’m focused on Israel’s security. No commission of inquiry established by previous governments for political agendas will alter that. I am prepared to endure your insults and investigations for the sake of Israel’s security.”

* It’s not clear what Netanyahu is implying, as there was no opposition to the purchase of the ships; there was just a highly opaque vendor selection process.

The commission’s recent findings have reminded us once more of a troubling pattern: over decades, Prime Minister Netanyahu has made autonomous decisions, apparently believing that he is exempt from some ‘unnecessary’ bureaucracy, research, oversight, and planning.

Let’s summarize once more.

Over seven years, Israel’s most strategically crucial and highly secretive military procurements have been exploited by a group of officials, lobbyists, and private individuals, pushing through multi-billion dollar deals amidst alleged corruption. This occurred directly under the prime minister’s watch, either due to his unawareness, complicity, or personal interests. Either of those scenarios would have resulted in immediate resignation in any normal democratic country.

The case directly involves two relatives of the Prime Minister, one of whom, taking advantage of his status as a close associate and often on his behalf, does not bother to mention that he is in fact the representative of the beneficiary company of the state contracts under discussion.

The prime minister himself is actively involved and sometimes initiates these deals, making decisions for the army and the defense ministry, confronting them, and sometimes not putting them on notice at all.

All of this is presented as an exceptional concern for Israel’s security, although at least one decision — the sale of submarines to Egypt — clearly contradicts this narrative. Any doubts about the legitimacy of these actions or suspicions regarding the prime minister’s motives, voiced by dozens of witnesses, are immediately painted as almost an attempted coup d’etat.

We are in a state of grave war today. Every decision carries profound implications for Israel’s security for decades to come. Every action and inaction today is literally a matter of life and death. Even amidst this war, cabinet members have already made explicit statements about the same questionable decision-making processes on many occasions.

A legitimate public inquiry and standard democratic oversight of governmental actions face ludicrous accusations of political motives and even conspiracy theories. However, if there is such an unwavering confidence in the integrity and righteousness of these decisions, why does the commission of inquiry provoke such fierce resistance and criticism? Let it do its job and shed light, then.

And now Netanyahu is acting against the establishment of a commission of inquiry on October 7. Then he will oppose a commission of inquiry into the actions of the current war. Especially if the composition of the commission will be determined, G-d forbid, by Judges Uzi Fogelman or Yitzhak Amit, and G-d forbid, its chairman will be Esther Hayut, who were never put in their place by the failed reform.

If nearly every recent process involves a preconceived list of culprits, labeling half of the country as misguided while positioning only one person as infallible, something is profoundly amiss. And that something could cost us the state if we don’t wake up.

Contents

Share

other materials