The level of hatred and aggressiveness in anti-Israel rhetoric worldwide after October 7 shocked and caught Israel and the entire Jewish diaspora off guard. Instead of universal empathy and support, Israel immediately encountered a striking amount of hostility, victim-blaming, and total misunderstanding even before the start of active military operations in response.

Let’s figure out what is wrong with many pro-Palestinian demonstrations post-October 7, based on what is currently happening in American colleges, breaking down where legitimate criticism of Israel ends and anti-Semitism begins, and how dangerous this phenomenon is.

What happened?

Besides massive solidarity actions with Israel at that time, an unprecedented wave of anti-Israel sentiment quickly emerged. Some might say unexpectedly, others might say predictably, but prestigious American universities became somewhat of a hub of acute anti-Israel sentiments.

Columbia University (New York) President Minouche Shafik was supposed to testify before the US House of Representatives Education Committee together with her colleagues from Harvard, Penn, and MIT as early as December 2023.

At that time, such responses as ‘it depends on the context’ and ‘if speech turns into conduct’ to questions whether calling for the genocide of Jews violates university rules became a global meme and one of the reasons for the resignations of Liz McGill from Pennsylvania and Claudine Gay from Harvard.

Minouche Shafik could not participate in the December hearings, and an additional session was held just two weeks ago, in mid-April. Dr. Shafik’s responses ignited a new wave of protests at the university.

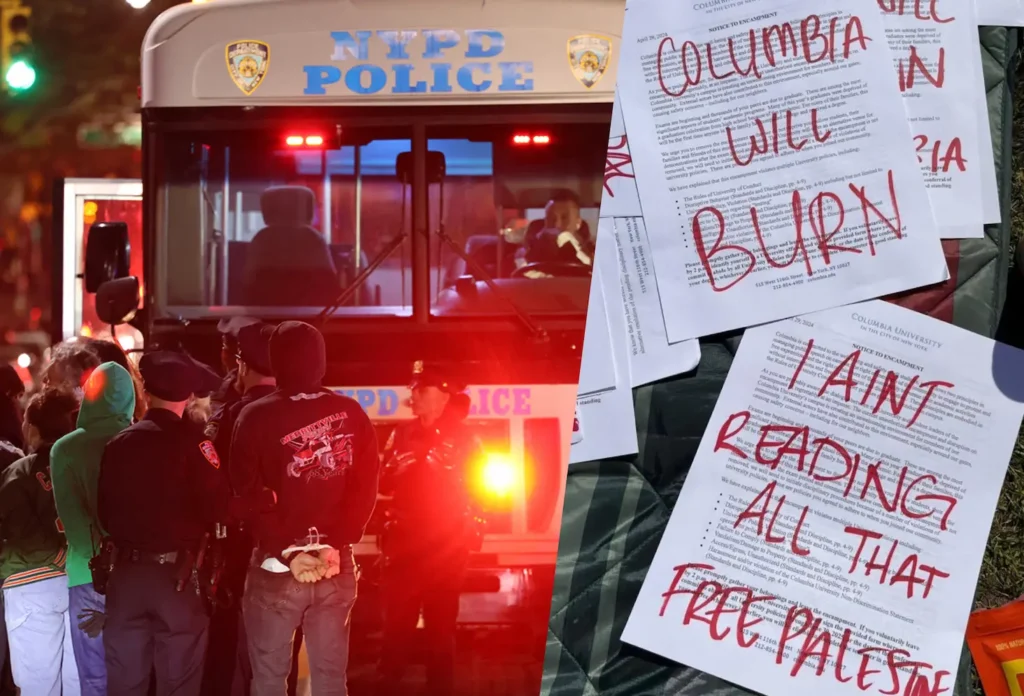

The university administration’s response to the protests, involving police intervention and arrests, spread the wave to other colleges in the country.

Source: CNN

The hearings consisted of a three-hour interrogation of Columbia University president and board members by permanent members of the committee and several other members of the US House of Representatives from both parties. The goal was to establish what steps the university administration was taking to combat anti-Semitism.

It’s worth noting that the hearings themselves are not the most pleasant or fair procedure for those being questioned. During these hearings, various politicians ask highly provocative and manipulatively phrased questions, cutting off answers mid-sentence, while the press is more than happy to use out-of-context words for headlines. Still, this is a reasonably effective tool for highlighting existing problems and calling for accountability from public structures and key organizations.

In March, the university released a report acknowledging a surge in anti-Semitic incidents after October 7 and proposing some changes to university rules addressing this issue. Apart from discussing the existing disciplinary measures against unauthorized demonstrations at the university and how they are applied, the commission focused on two, perhaps key questions:

- Which slogans during demonstrations can be interpreted as anti-Semitic?

- How should solidarity with actions of terrorist groups by university students and workers be assessed?

Despite all respondents unanimously acknowledging, unlike the December hearings, that calls for the genocide of Jews contradict university rules regardless of context, there was a vivid discussion around formulations.

For instance, the notoriously known chant ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,’ according to Dr. Shafik, is not perceived by everyone as offensive and does not necessarily advocate for violence in the form of the Jewish state elimination between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

Another example is calls for intifada. Some argue that intifada has many meanings, including non-violent methods of resistance. Still, for Jewish and especially Israeli students, this word is inseparably linked to terrorism and violence directed against the Jewish population of Israel.

Moreover, during the hearings, names of several professors were mentioned who had expressed support for Hamas’ actions after October 7 in one way or another.

Professor Joseph Massad, of Jordanian-Palestinian origin, who has been teaching at the university for several decades, published an article on October 8 expressing his admiration for the ‘innovative approaches’ of Hamas’s resistance and the fact of seizing Israeli villages. In his statement, however, Massad claims that his article is purely descriptive and factual and does not provide an assessment of any actions.

Just invited Dr. Mohamed Abdo, in his Facebook post on October 11, while criticizing Islamists for their radical position on LGBTQ issues, nevertheless supports, albeit violent, but necessary actions of ‘resistance’ for ‘decolonization’ and even expresses solidarity ‘to a certain extent’ with Hamas, Hezbollah, and Islamic Jihad.

President Shafik evasively replied that measures had been or would be taken against both professors. Prof. Massad was allegedly removed from the university’s Academic Committee on Arts and Sciences chair, although he claims no one has spoken to him. Regarding Dr. Abdo, Shafik stated that his invitation has been revoked, and he will no longer teach at Columbia University.

These responses ignited an uproar within left-wing academic circles, accusing Shafik of succumbing to political pressure and the politicians themselves of engaging in a ‘new McCarthyism’ (an aggressive campaign against communist views in the US during the 1940s and 1950s) and infringing on academic freedom of expression.

That, apparently, also served as a spark for student protests.

What is the problem with the protests?

In addition to the technical details of violating university rules and regulations regarding demonstrations, the current wave of protests, like many pro-Palestinian rallies since October 7, has one key issue.

Protesters often not only advocate for ending the war or criticize Israel for specific actions, or express solidarity with Palestinians and voice support for establishing a Palestinian state based on an acceptable internationally ‘two states solution,’ which would be a legitimate expression of a position one can agree or disagree with.

Instead, protests almost always contain some anti-Semitic slogans and calls that can be classified in several directions.

Attacks on Jews who do not express anti-Israeli views. Many Jewish students complain that they either become victims of attacks on them personally as Jews, or experience fear and rejection in the atmosphere that has emerged, forcing them to think twice about expressing pro-Israeli positions and wearing visual symbols of Judaism or even solidarity with Israeli hostages.

Often behind anti-Israeli positions hides the most primitive hatred and prejudice towards the Jewish people as a whole, belief in stereotypes, and various conspiracy theories about Jewish omnipotence as a global evil. Nonetheless, protesters like to emphasize that their protest is only anti-Zionist in nature and cite the participation of Jews in their actions, such as the organization Jewish Voices for Peace with an active anti-Israeli stance. This brings us to the second point.

Delegitimization of Zionism and the State of Israel as such. The statement that the State of Israel, in general, has no right to exist is a fundamental premise for both most anti-Israeli protests and Palestinian propaganda. It is where this quite mind-boggling meeting and imaginary unity of goals between radical Islamists and progressive activists takes place.

Viewing the nature of Palestinian-Israeli relations through models and terms of post-colonial theory: oppressors and victims, exploiters and enslaved, strong and weak – protesters assume that the State of Israel, allegedly imperialist, colonial manifestation, has no place in the modern world, and the Palestinian people, as its supposedly oppressed victims, seeks liberation.

History is subject to revision in this paradigm, and broad international recognition of Israel is irrelevant. Zionism is seen as a movement primarily aimed at allegedly displacing Palestinians from their land and establishing hegemony over them. Any action by the Jewish state throughout history and today is viewed as inherently illegitimate, supposedly dictated only by motives of further oppression or, even worse – genocide of Palestinians. This brings us to the third point.

Calls for violence and expressions of solidarity with terrorist groups. In the paradigm of many protesters, if Israel and Zionism are seen as something so hostile, then any, even the most radical and violent methods of fighting against it are considered acceptable. Therefore, there are no contradictions in supporting Hamas or even declaring ‘we are all Hamas,’ dressing in the symbols of terrorist organizations (seen as liberation movements by protesters), calling for a global intifada, wishing death to Zionism and even Zionists.

Despite protesters attempting to justify themselves by claiming they have nothing against Jews, anti-Semitism is a complex and multifaceted concept that, unfortunately, does not remain static. According to the working definition of anti-Semitism developed by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), adopted by most Western countries and American states as a benchmark, anti-Semitism includes not only dislike towards Jews as individuals but also ‘denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of the State of Israel is a racist endeavor.’ Therefore, anti-Zionism is also equated with anti-Semitism.

So what, one can’t even criticize Israel?

Many people from both sides often err in answering this question. No, not all criticism of Israel is a manifestation of anti-Semitism. The IHRA itself clarifies this in its explanations of the definition: ‘Criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as anti-Semitic.’

Despite the thin line, in reality, the test is quite simple: does the criticizing party recognize the right of the Jewish people to self-determination and, consequently, the right of Israel to exist?

If the criticism refers to any action (or inaction) by Israel, such as criticism of military actions, criticism of inaction in advancing the peace process with demands to move it forward, criticism of the settlement movement, or even demands to revert to the 1967 borders, it may be pretty controversial and inappropriate in some cases, but it is still a legitimate position acknowledging Israel within certain borders.

However, if the basis of the criticism is the belief that Israel inside any borders is an illegitimate state entity that must eventually cease to exist – this is anti-Semitism.

So, how should we view calls for boycotts, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) policies that define current protest demands from college administrations?

Note The protesters of the current wave demand that universities cease academic collaboration with Israel and divest endowment funds from companies associated with the Jewish state. We are talking about significant money; for example, Columbia University’s endowment fund reaches $14 billion. However, if we consider university investment portfolios in all companies even remotely associated with Israel, this includes American tech giants such as Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon, and others. Moreover, not all universities disclose this information openly. Most universities immediately reject students’ demands, but some have agreed to consider specific student proposals if protests cease (e.g., Brown University). At the moment, it is unlikely that this will lead to real action.

The same test applies here. If the motivation for political and economic pressure on Israel is an attempt to persuade it to abandon certain policies or implement others, and the pressure is limited and temporary, then these demands, however controversial, are not much different from sanctions against other countries and their authorities.

Yet, if the goal of the pressure is a total war aimed at the destruction of Israel on the political and economic fronts, then such aspirations are equivalent to the destruction of any other state on the world map. But it would be ridiculous if similar calls for destruction were directed towards, say, Venezuela, Canada, Algeria, or Indonesia. Unfortunately, when it comes to Israel, we have to clarify this.

An additional question arises: why is it specifically Israel that becomes a magnet for what seems like global attention, extensive demands, and double standards? Many see anti-Semitism in this, but one must be particularly cautious not to perceive every manifestation as intolerance towards Jews so as not to dilute or devalue this term but to keep it within clear, definite boundaries for all.

How dangerous is all of this? And what should be done about it?

Any fanatical conviction is always dangerous. The unwillingness to subject one’s views to periodic scrutiny and a healthy dose of doubt, and contrarily, the tendency to lock the doors of one’s beliefs with a soundproof lock against others’ voices, is a dangerous phenomenon for everyone without exception, and Israeli society suffers from this no less.

Returning to college protests, this is undoubtedly a challenging juncture for Jewish and Israeli students and a significant test for the American system of education, justice, and legislation. Undoubtedly, the degree of aggression and conviction in students’ rhetoric is surprising; despite what may seem like a dire situation, several points must be considered.

No matter how loud the protests may be, assessing their representativeness is difficult. Yes, protests have erupted across almost the entire country, but it’s worth mentioning that around 20 million students enroll in the US each year; therefore, the absolute majority do not participate in these protests, and this phenomenon is far from widespread.

Furthermore, it’s challenging to gauge the seriousness of the participants’ motivations in these protests: for whom is this truly a principle and an anti-Israel conviction, and for whom is it solidarity (since the wave rose broadly after police actions), a tribute to fashion, or a good opportunity to skip classes?

According to several surveys, such extreme rhetoric remains a relatively marginal phenomenon. Yes, opinions in the US are divided between sympathy for Israelis and Palestinians, but direct support for Hamas and similar terrorist groups is far from being widespread.

Despite the typical ideological wandering in academic circles, political elites are still largely pro-Israel. Concerns about generational shifts in politics and fears that leaders of such protests, bearers of aggressive views and rhetoric, will gain significant political power have been voiced for at least a decade. Yet, mainstream politics is still far from reachable for such figures, although we shouldn’t underestimate the trend of ignorant populism and shallow politics from all sides, both right and left.

Nonetheless, it’s impossible not to note that ‘diplomatic clouds’ are gathering for Israel, mainly due to the heavy, prolonged war – a highly losing recipe for any foreign policy of Israel, which attracts too much attention even in peaceful times. This does not diminish, however, the role of profoundly weak diplomacy in recent years, the absence of any strategy, and proactive steps.

Clearly, a total reassessment of methods for shaping Israel’s international image is required. And it’s evident that populist reactions, grudges, grievances, and labeling any criticism towards Israel as anti-Semitism are as distant from smart and tricky foreign policy as global society is from unconditional love for the Jewish state.

Share

other materials