Why did we choose to tackle the issue of settlements? And why was it so hard?

I’ll start with a personal confession: many places in Judea and Samaria are very close to my heart.

I have a deep affection for Hebron. I’ve been there quite a few times, even led tours to introduce others to this remarkable place. I would tell the incredible story of Hebron’s Jewish community, though I must admit I approached the complexities of the conflict with a certain bias.

Nowhere else does my prayer feel as heartfelt as it does in the Cave of the Patriarchs, and nowhere else do I feel the presence of ancient Jewish history as vividly as I do there.

I have always been deeply moved by the dramatic history of the Gush Etzion kibbutzim, which fell on May 13, 1948, just one day before Israel declared its independence. It’s impossible not to be touched by the story of Hanan Porat, one of the leaders of the settlement movement. Evacuated from Kfar Etzion as a child in 1948, he later fought in the battles for Jerusalem in 1967, and went on to rebuild the very settlement where his ancestors had perished.

On my father’s grave rests a stone from Mount Eival (near Nablus)—a site of profound significance in the biblical narrative.

There are countless remarkable places and incredible stories in these lands, each one steeped in ancient Jewish history, which holds deep meaning for me.

This item has been challenging for me for two reasons: one is more personal, while the other concerns the thate of our nation. Yet, both aspects are closely interconnected.

The first reason stems from a personal journey I’ve been on for several years—a realization that many of my previous beliefs were rooted in ignorance or a reluctance to seek deeper understanding, preferring to remain on the surface. During my visits to various locations in Judea and Samaria, I often failed to question the foundations on which these places were established.

I was deeply immersed in the personal significance of these lands and their historical importance to me. This connection provided a perspective that spanned millennia, drawing my attention away from the more immediate questions regarding their relevance—not just to Jewish history, but to the modern Jewish state here and now.

In this regard, however, I have also taken a convenient stance. It argues that we were not the ones who initiated the Six-Day War, nor were we responsible for blocking the Strait of Tiran or threatening our neighbors with total annihilation. We certainly did not open the Jordanian front. Therefore, the victors in this conflict are not to be judged. Additionally, this stance points out that the Palestinians themselves seem unable to decide what they want, having rejected several proposed state options in favor of warfare. With no partner for peace, the questions of there is still no peace should be directed elsewhere.

This simplistic view of historical processes, while it may hold some justification, is comfortable precisely because it obscures our role in the conflict and our involvement in its resolution. It offers a tempting sense of righteousness, shifts the burden of responsibility, and postpones the resolution of the conflict into the distant future. Yet, it neglects to address the seemingly obvious questions: what have we been doing all this time, where are we headed, and what are we counting on?

My genuine interest in the legal foundations of settlement activity was sparked a year ago while I was preparing a piece on the judicial overhaul. During this time, I examined historical, precedent-setting Supreme Court decisions, including the significant cases involving the settlements of Beit El and Elon Moreh.

However, it wasn’t until Israel’s key partners started imposing sanctions and legal challenges loomed over our country that I began to take the topic seriously. I finally attempted to understand what the world was saying and what we had been overlooking. Until then, I, like many others, had opted to look away and avoid deeper reflection on the issue.

To be honest, until October 7, this was a rather comfortable stance, particularly for someone who arrived here after Operation Protective Edge in 2014. While there were occasional outbreaks of violence, it was still possible to engage in abstract discussions about the conflict, debate the terminology of different territories, and take pride in the certainty of one’s position in times of self-created, illusory stability.

The initial reaction to October 7 was a reinforcement of previous positions. It seemed to provide yet another piece of evidence: what kind of peace or solution to the conflict can we realistically discuss?

But since then, reality has begun to descend with that same hard but obvious questions: what have we been doing all this time, where are we headed, and what are we counting on?

One can present a thousand justified arguments about how peace is unreachable either now or in the foreseeable future. However, an honest assessment of reality is that millions of people from two different national groups inhabit the same piece of land, and neither group is going anywhere. Both are willing to fight and die for this land, as as has been proven time after time.

Until recently, we argued that our side has always been willing to pursue a two-state solution, if only the other side opted for peace. Let’s assume that is still true, though I’m not entirely sure anymore. But what have we been doing all this time, and what were we hoping to achieve? How does the settlement movement align with this thesis? Have we not been making the two-state solution increasingly unattainable, regardless of whether the Palestinians are prepared for it or not?

What is a settlement enterprise if not just a desire to claim territory under the guise of security reasons and the notion that peace is unattainable here and now?

What is a settlement enterprise if not the perpetuation of a territorial problem?

What is a settlement enterprise if not decades of unresolved national dilemma, reflecting our repeated indecision on what we truly want and where we are headed as a nation?

If we still genuinely aspire to peace, respect the another people’s right of self-determination (as long as it doesn’t threaten our existence), and view ourselves as part of the civilized, democratic world governed by the rule of law—while seeking cooperation and support from it—then perhaps we should at least pause activities that the rest of the world deems illegal. We need to move beyond the bravado of our supposed invincibility and begin contemplating how we can strive for peace, even under these challenging circumstances.

Yes, strive, not just talk about it, since peace is not a rosy dream that descends from the heavens for those who passively wish for it. It demands action, strategic planning, trial and error, patience, and unwavering determination. Like sports or any healthy habit, peace cannot be abandoned after the first failed attempt. If we only depict ourselves as those who yearn for peace while the cruel world attacks us, we become nothing more than naive utopians, waiting for peace to materialize on its own, if and when all the evil forces in the world suddenly see the Truth.

If we are still a truly peace-loving nation, as we so often strive to convince the world, then our actions must align with our words. The pursuit of peace should not be reduced to mere slogans or sarcastic jabs at 90s political agendas (“oh, those poor, naive leftists”); it should be rather reinstalled as a fundamental part of our current political strategies and future plans. Geopolitical actions must be evaluated based on whether they bring us closer to or further away from the prospect of peace.

Moreover, any unjustified violence on our part should be immediately halted and prosecuted. This is what a nation founded on the ideals of peace does—not just talks about it when it’s convenient. Only then could we honestly look the world in the eyes and say we are truly seeking peace in both words and actions, and not just selling nice stories while stoking a never-ending war in the ‘backyard’.

In my view, following the tragedy of October 7, our focus should not be on revenge, punishment, or hatred, but rather on peace—genuine peace, achievable peace on acceptable terms, based on a decades-long plans. This must once again become the ideal we strive for as a society. The pursuit of peace should be our primary goal, with appropriate means and solutions developed to support it. We need to reevaluate all our current strategies and abandon those that have only fueled further violence.

But if all of this is irrelevant—if we, as a society, continue to mock these ideals and dismiss them as some “leftist” notions; if we are waging a holy war, fighting to the last person for every scrap of this land; if our goal is to crush the other nation and assert our dominance, proving to ourselves and others that everything here is rightfully ours while denying the very existence of the other nation—then let us at least be honest with ourselves and the world. Let us declare what our true aspirations are and be prepared to face the consequences.

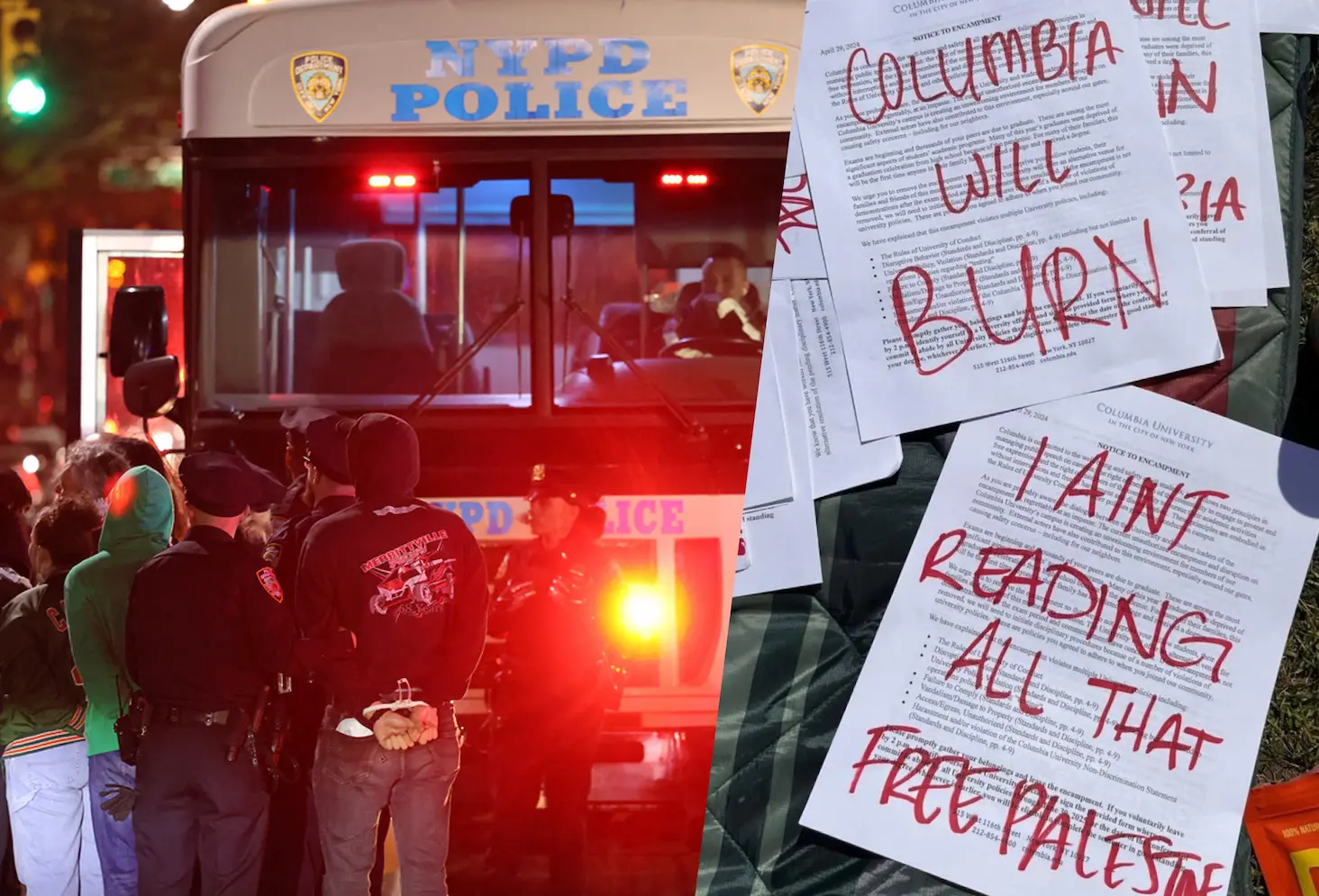

Let’s not tell the world how peaceful and enlightened we are when radical settler groups, who forcibly seize territory, demolish villages, and glorify violence along with their sense of “chosenness,” are becoming the new face of Zionism, normalized by our resounding silence.

If fighting this shameful phenomenon of settler violence—let alone the questionable legality of settler enterprise as a whole—is considered unpopular, then let’s stop downplaying and whitewashing it with petty excuses about an extreme, unrepresentative minority. Let’s face the facts and say it openly: this is what we want. The rule of law is of no interest to us; we aim to apply it selectively and make it legal.

There’s also little value in lamenting how our dream of peace confronts a wall of misunderstanding when our ministers openly advocate for bloodthirsty revenge, punishment, and humiliation. This isn’t force for peace; it’s merely force for the sake of force.

We are quick to accuse everyone of hypocrisy—be it the BBC, CNN, the Palestinians, or anyone else—but we fail to recognize that we do exactly the same thing, blinded by an unwavering sense of self-righteousness. It genuinely shocks us each time the entire world suddenly turns against us and tells us, as Joe Biden gently put it: “stop bullshitting me.”

What I dislike most is indirectness, insincerity, hypocrisy, and ulterior motives. On a personal level, I prefer to filter out people who exhibit this kind of behavior. Yet, this is how we often conduct ourselves on a national scale. Even worse, it has also infiltrated our internal public discourse.

And this is the second reason why this item was particularly challenging for me. At the public level, we have stopped discussing it directly, opting instead for hints, euphemisms, and caveats that mystify and blur the entire issue. While preparing this material, I found myself repeatedly searching for pitfalls and choosing my words with unnecessary caution, even resorting to some sort of self-censorship as I pondered what should or shouldn’t be written. Isn’t this a clearest indicator that something is amiss? This topic has become a taboo, a real minefield of ideas and perspectives, where any expressed thought—or even worse, any term or name used—leads to labeling, discrediting, or even harassment.

The lack of direct and honest conversation and silent movement in opposite directions is destroying the foundations and consensus of our society. Each side is pulling this patchwork quilt in its own direction. Through Oslo and Rabin’s assassination, through the peace experiment of the nineties and noughties that was not elaborated, not fully realized and traumatic, through the Gaza withdrawal, through the “miracle-era ” policy of settlement permissiveness – the unfinished and halfway abandoned conversation has moved to the level of grievances and unspoken passive aggression cynically and irresponsibly used by the populists of the last decade.

The absence of direct and honest conversation, coupled with a silent drift in opposing directions, is eroding the foundations and consensus of our society. From the Oslo Accords and Rabin’s assassination to the unfulfilled and traumatic peace experiment of the ’90 and early ’00s, through the Gaza withdrawal and the “miracle era” policy of settlement permissiveness, this half-abandoned dialogue has devolved into mutual resentments and unspoken passive aggression, cynically and irresponsibly bloated by the populists of the last decade.

However, we have no choice but to engage in an honest and open-minded conversation about “what we want to be when we grow up.” Metaphorically speaking, this is the moment when a reasonable adult needs to sit down with a restless teenager and explain that while it’s possible to live one day at a time without considering the consequences of one’s actions, there comes a point when that approach is no longer sustainable and could lead to self-destruction.

Before this conversation even begins, everyone needs to recognize the urgent need for it. We are indeed in deep water, and the fattened elephant in the room has grown to enormous proportions, threatening to leave us with no space at all. This conversation must be approached with a profound understanding that no one, on either side, possesses the magic key or the one correct solution for today. It is with this humble and honest acknowledgment that we must approach our brainstorming about the future. To make progress, we need to agree, at least in broad terms, on where we want to go and start taking careful steps in that direction.

It may be that we will never agree and never find a common denominator after so many years of terrible irresponsibility and petty politicking by our leaders; their ongoing failure to grasp that any decision—or indecision—made today can have repercussions for decades to come; a tendency to sharpen corners rather than smooth them out; an “us versus them” mentality instead of a “we” approach; and numerous fundamental mistakes along the way. But at least we will try.

Writing this material was not easy, but I approached it with a pure heart. I value honesty, and the truth always holds greater importance for me, even when it’s inconvenient. I hope this is what our society will strive for: to realize that a bitter, painful truth is indeed better than a sweet delusion. I also hope we come to recognize that a hard and uncomfortable conversation is always preferable to unspoken, potentially explosive tension.